15 Money and Banking

The discussion of money and banking is a central component in studying macroeconomics. At this point, you should have firmly in mind the main goals of macroeconomics from Welcome to Economics!: economic growth, low unemployment, and low inflation. We have yet to discuss money and its role in helping to achieve our macroeconomic goals.

You should also understand Keynesian and neoclassical frameworks for macroeconomic analysis and how we can embody these frameworks in the aggregate demand/aggregate supply (AD/AS) model. With the goals and frameworks for macroeconomic analysis in mind, the final step is to discuss the two main categories of macroeconomic policy: monetary policy, which focuses on money, banking and interest rates; and fiscal policy, which focuses on government spending, taxes, and borrowing. This chapter discusses what economists mean by money, and how money is closely interrelated with the banking system. Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation furthers this discussion.

THE MANY DISGUISES OF MONEY: FROM COWRIES TO BITCOINS

Here is a trivia question: In the history of the world, what item did people use for money over the broadest geographic area and for the longest period of time? The answer is not gold, silver, or any precious metal. It is the cowrie, a mollusk shell found mainly off the Maldives Islands in the Indian Ocean. Cowries served as money as early as 700 B.C. in China. By the 1500s, they were in widespread use across India and Africa. For several centuries after that, cowries were the means for exchange in markets including southern Europe, western Africa, India, and China: everything from buying lunch or a ferry ride to paying for a shipload of silk or rice. Cowries were still acceptable as a way of paying taxes in certain African nations in the early twentieth century.

What made cowries work so well as money? First, they are extremely durable—lasting a century or more. As the late economic historian Karl Polyani put it, they can be “poured, sacked, shoveled, hoarded in heaps” while remaining “clean, dainty, stainless, polished, and milk-white.” Second, parties could use cowries either by counting shells of a certain size, or—for large purchases—by measuring the weight or volume of the total shells they would exchange. Third, it was impossible to counterfeit a cowrie shell, but dishonest people could counterfeit gold or silver coins by making copies with cheaper metals. Finally, in the heyday of cowrie money, from the 1500s into the 1800s, governments, first the Portuguese, then the Dutch and English, tightly controlled collecting cowries. As a result, the supply of cowries grew quickly enough to serve the needs of commerce, but not so quickly that they were no longer scarce. Money throughout the ages has taken many different forms and continues to evolve even today. What do you think money is?

15.1 Defining Money by Its Functions

Money for the sake of money is not an end in itself. You cannot eat dollar bills or wear your bank account. Ultimately, the usefulness of money rests in exchanging it for goods or services. As the American writer and humorist Ambrose Bierce (1842–1914) wrote in 1911, money is a “blessing that is of no advantage to us excepting when we part with it.” Money is what people regularly use when purchasing or selling goods and services, and thus both buyers and sellers must widely accept money. This concept of money is intentionally flexible, because money has taken a wide variety of forms in different cultures.

15.1.1 Barter and the Double Coincidence of Wants

To understand the usefulness of money, we must consider what the world would be like without money. How would people exchange goods and services? Economies without money typically engage in the barter system. Barter—literally trading one good or service for another—is highly inefficient for trying to coordinate the trades in a modern advanced economy. In an economy without money, an exchange between two people would involve a double coincidence of wants, a situation in which two people each want some good or service that the other person can provide. For example, if an accountant wants a pair of shoes, this accountant must find someone who has a pair of shoes in the correct size and who is willing to exchange the shoes for some hours of accounting services. Such a trade is likely to be difficult to arrange. Think about the complexity of such trades in a modern economy, with its extensive division of labor that involves thousands upon thousands of different jobs and goods.

Another problem with the barter system is that it does not allow us to easily enter into future contracts for purchasing many goods and services. For example, if the goods are perishable it may be difficult to exchange them for other goods in the future. Imagine a farmer wanting to buy a tractor in six months using a fresh crop of strawberries. Additionally, while the barter system might work adequately in small economies, it will keep these economies from growing. The time that individuals would otherwise spend producing goods and services and enjoying leisure time they spend bartering.

15.1.2 Functions for Money

Money solves the problems that the barter system creates. (We will get to its definition soon.) First, money serves as a medium of exchange, which means that money acts as an intermediary between the buyer and the seller. Instead of exchanging accounting services for shoes, the accountant now exchanges accounting services for money. The accountant then uses this money to buy shoes. To serve as a medium of exchange, people must widely accept money as a method of payment in the markets for goods, labor, and financial capital.

Second, money must serve as a store of value. In a barter system, we saw the example of the shoemaker trading shoes for accounting services. However, she risks having her shoes go out of style, especially if she keeps them in a warehouse for future use—their value will decrease with each season. Shoes are not a good store of value. Holding money is a much easier way of storing value. You know that you do not need to spend it immediately because it will still hold its value the next day, or the next year. This function of money does not require that money is a perfect store of value. In an economy with inflation, money loses some buying power each year, but it remains money.

Third, money serves as a unit of account, which means that it is the ruler by which we measure values. For example, an accountant may charge $100 to file your tax return. That $100 can purchase two pair of shoes at $50 a pair. Money acts as a common denominator, an accounting method that simplifies thinking about trade-offs.

Finally, another function of money is that it must serve as a standard of deferred payment. This means that if money is usable today to make purchases, it must also be acceptable to make purchases today that the purchaser will pay in the future. Loans and future agreements are stated in monetary terms and the standard of deferred payment is what allows us to buy goods and services today and pay in the future. Thus, money serves all of these functions— it is a medium of exchange, store of value, unit of account, and standard of deferred payment.

15.1.3 Commodity versus Fiat Money

Money has taken a wide variety of forms in different cultures. People have used gold, silver, cowrie shells, cigarettes, and even cocoa beans as money. Although we use these items as commodity money, they also have a value from use as something other than money. For example, people have used gold throughout the ages as money although today we do not use it as money but rather value it for its other attributes. Gold is a good conductor of electricity and the electronics and aerospace industry use it. Other industries use gold too, such as to manufacture energy efficient reflective glass for skyscrapers and is used in the medical industry as well. Of course, gold also has value because of its beauty and malleability in creating jewelry.

As commodity money, gold has historically served its purpose as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and as a unit of account. Commodity-backed currencies are dollar bills or other currencies with values backed up by gold or other commodities held at a bank. During much of its history, gold and silver backed the money supply in the United States. Interestingly, antique dollars dated as late as 1957, have “Silver Certificate” printed over the portrait of George Washington, as Figure 15.1 shows. This meant that the holder could take the bill to the appropriate bank and exchange it for a dollar’s worth of silver.

As economies grew and became more global in nature, the use of commodity monies became more cumbersome. Countries moved towards the use of fiat money. Fiat money has no intrinsic value, but is declared by a government to be a country's legal tender. The United States’ paper money, for example, carries the statement: “THIS NOTE IS LEGAL TENDER FOR ALL DEBTS, PUBLIC AND PRIVATE.” In other words, by government decree, if you owe a debt, then legally speaking, you can pay that debt with the U.S. currency, even though it is not backed by a commodity. The only backing of our money is universal faith and trust that the currency has value, and nothing more.

- Money is what people in a society regularly use when purchasing or selling goods and services. If money were not available, people would need to barter with each other, meaning that each person would need to identify others with whom they have a double coincidence of wants—that is, each party has a specific good or service that the other desires.

- Money serves several functions: a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value, and a standard of deferred payment. There are two types of money: commodity money, which is an item used as money, but which also has value from its use as something other than money; and fiat money, which has no intrinsic value, but is declared by a government to be the country's legal tender.

- What are the four functions that money serves?

- How does the existence of money simplify the process of buying and selling?

- What is the double-coincidence of wants?

15.2 Measuring Money: Currency, M1 and M2

Cash in your pocket certainly serves as money; however, what about checks or credit cards? Are they money, too? Rather than trying to state a single way of measuring money, economists offer broader definitions of money based on liquidity. Liquidity refers to how quickly you can use a financial asset to buy a good or service. For example, cash is very liquid. You can use your $10 bill easily to buy a hamburger at lunchtime. However, $10 that you have in your savings account is not so easy to use. You must go to the bank or ATM machine and withdraw that cash to buy your lunch. Thus, $10 in your savings account is less liquid.

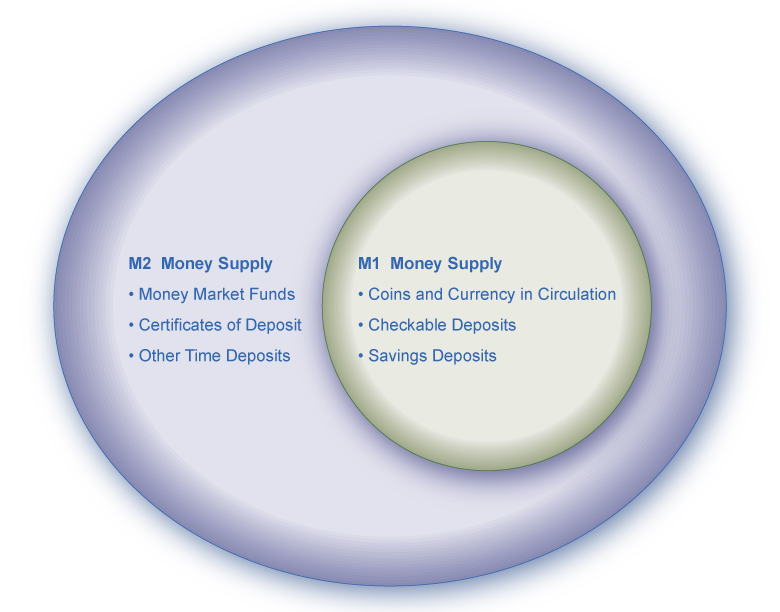

The Federal Reserve Bank, which is the central bank of the United States, is a bank regulator and is responsible for monetary policy and defines money according to its liquidity. There are two definitions of money: M1 and M2 money supply. Historically, M1 money supply included those monies that are very liquid such as cash, checkable (demand) deposits, and traveler’s checks, while M2 money supply included those monies that are less liquid in nature; M2 included M1 plus savings and time deposits, certificates of deposits, and money market funds. Beginning in May 2020, the Federal Reserve changed the definition of both M1 and M2. The biggest change is that savings moved to be part of M1. M1 money supply now includes cash, checkable (demand) deposits, and savings. M2 money supply is now measured as M1 plus time deposits, certificates of deposits, and money market funds.

M1 money supply includes coins and currency in circulation—the coins and bills that circulate in an economy that the U.S. Treasury does not hold at the Federal Reserve Bank, or in bank vaults. Closely related to currency are checkable deposits, also known as demand deposits. These are the amounts held in checking accounts. They are called demand deposits or checkable deposits because the banking institution must give the deposit holder his money “on demand” when the customer writes a check or uses a debit card. These items together—currency, and checking accounts in banks—comprise the definition of money known as M1, which the Federal Reserve System measures daily.

As mentioned, M1 now includes savings deposits in banks, which are bank accounts on which you cannot write a check directly, but from which you can easily withdraw the money at an automatic teller machine or bank.

A broader definition of money, M2 includes everything in M1 but also adds other types of deposits. Many banks and other financial institutions also offer a chance to invest in money market funds, where they pool together the deposits of many individual investors and invest them in a safe way, such as short-term government bonds. Another ingredient of M2 are the relatively small (that is, less than about $100,000) certificates of deposit (CDs) or time deposits, which are accounts that the depositor has committed to leaving in the bank for a certain period of time, ranging from a few months to a few years, in exchange for a higher interest rate. In short, all these types of M2 are money that you can withdraw and spend, but which require a greater effort to do so than the items in M1.

Figure 15.2 should help in visualizing the relationship between M1 and M2. Note that M1 is included in the M2 calculation.

The Federal Reserve System is responsible for tracking the amounts of M1 and M2 and prepares a weekly release of information about the money supply. To provide an idea of what these amounts sound like, according to the Federal Reserve Bank’s measure of the U.S. money stock, at the end of February 2015, M1 in the United States was $3 trillion, while M2 was $11.8 trillion.

Table Table 15.1 provides more recent figures and a breakdown of the portion of each type of money that comprised M1 and M2 in October 2021, as provided by the Federal Reserve Bank.

| Components of M1 in the U.S. (October 2018) | $ billions |

|---|---|

| Currency held by the public | $2,065 billion |

| Demand deposits | $4,002 billion |

| Savings and other liquid deposits | $12,154 billion |

| Total of M1 | $19,221 billion |

| Components of M2 in the U.S. (October 2018) | $ billions |

|---|---|

| M1 | $19,221 billion |

| Money market retail funds | $1,027 billion |

| Small time deposits | $120 billion |

| Total of M2 | \(\approx\) $20,000 billion |

The lines separating M1 and M2 can become a little blurry. Sometimes businesses do not treat elements of M1 alike. For example, some businesses will not accept personal checks for large amounts, but will accept traveler’s checks or cash. Changes in banking practices and technology have made the savings accounts in M2 more similar to the checking accounts in M1. For example, some savings accounts will allow depositors to write checks, use automatic teller machines, and pay bills over the internet, which has made it easier to access savings accounts. As with many other economic terms and statistics, the important point is to know the strengths and limitations of the various definitions of money, not to believe that such definitions are as clear-cut to economists as, say, the definition of nitrogen is to chemists.

Where does “plastic money” like debit cards, credit cards, and smart money fit into this picture? A debit card, like a check, is an instruction to the user’s bank to transfer money directly and immediately from your bank account to the seller. It is important to note that in our definition of money, it is checkable deposits that are money, not the paper check or the debit card. Although you can make a purchase with a credit card, the financial institution does not consider it money but rather a short term loan from the credit card company to you. When you make a credit card purchase, the credit card company immediately transfers money from its checking account to the seller, and at the end of the month, the credit card company sends you a bill for what you have charged that month. Until you pay the credit card bill, you have effectively borrowed money from the credit card company. With a smart card, you can store a certain value of money on the card and then use the card to make purchases. Some “smart cards” used for specific purposes, like long-distance phone calls or making purchases at a campus bookstore and cafeteria, are not really all that smart, because you can only use them for certain purchases or in certain places.

In short, credit cards, debit cards, and smart cards are different ways to move money when you make a purchase. However, having more credit cards or debit cards does not change the quantity of money in the economy, any more than printing more checks increases the amount of money in your checking account.

One key message underlying this discussion of M1 and M2 is that money in a modern economy is not just paper bills and coins. Instead, money is closely linked to bank accounts. The banking system largely conducts macroeconomic policies concerning money. The next section explains how banks function and how a nation’s banking system has the power to create money.

We measure money with several definitions: - M1 includes currency and money in checking accounts (demand deposits) and savings accounts. - Traveler’s checks are also a component of M1, but are declining in use.

M2 includes all of M1, plus time deposits like certificates of deposit, and money market funds.

What components of money do we count as part of M1?

What components of money do we count in M2?

For the following list of items, indicate if they are in M1, M2, or neither:

a. Your \$5,000 line of credit on your Bank of America card b. \$50 dollars' worth of traveler's checks you have not used yet c. \$1 in quarters in your pocket d. \$1200 in your checking account e. \$2000 you have in a money market account

15.3 The Role of Banks

Somebody once asked the late bank robber named Willie Sutton why he robbed banks. He answered: “That’s where the money is.” While this may have been true at one time, from the perspective of modern economists, Sutton is both right and wrong. He is wrong because the overwhelming majority of money in the economy is not in the form of currency sitting in vaults or drawers at banks, waiting for a robber to appear. Most money is in the form of bank accounts, which exist only as electronic records on computers. From a broader perspective, however, the bank robber was more right than he may have known. Banking is intimately interconnected with money and consequently, with the broader economy.

Banks make it far easier for a complex economy to carry out the extraordinary range of transactions that occur in goods, labor, and financial capital markets. Imagine for a moment what the economy would be like if everybody had to make all payments in cash. When shopping for a large purchase or going on vacation you might need to carry hundreds of dollars in a pocket or purse. Even small businesses would need stockpiles of cash to pay workers and to purchase supplies. A bank allows people and businesses to store this money in either a checking account or savings account, for example, and then withdraw this money as needed through the use of a direct withdrawal, writing a check, or using a debit card.

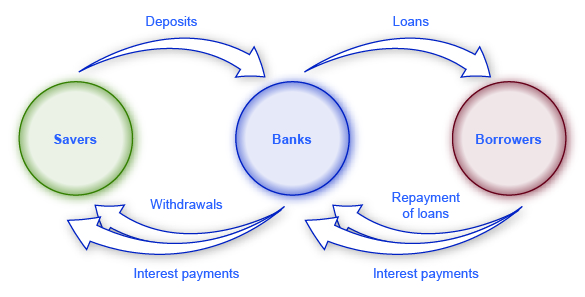

Banks are a critical intermediary in what we call the payment system, which helps an economy exchange goods and services for money or other financial assets. Also, those with extra money that they would like to save can store their money in a bank rather than look for an individual who is willing to borrow it from them and then repay them at a later date. Those who want to borrow money can go directly to a bank rather than trying to find someone to lend them cash. Transaction costs are the costs associated with finding a lender or a borrower for this money. Thus, banks lower transactions costs and act as financial intermediaries—they bring savers and borrowers together. Along with making transactions much safer and easier, banks also play a key role in creating money.

15.3.1 Banks as Financial Intermediaries

An “intermediary” is one who stands between two other parties. Banks are a financial intermediary—that is, an institution that operates between a saver who deposits money in a bank and a borrower who receives a loan from that bank. Financial intermediaries include other institutions in the financial market such as insurance companies and pension funds, but we will not include them in this discussion because they are not depository institutions, which are institutions that accept money deposits and then use these to make loans. All the deposited funds mingle in one big pool, which the financial institution then lends. Figure 15.3 illustrates the position of banks as financial intermediaries, with deposits flowing into a bank and loans flowing out. Of course, when banks make loans to firms, the banks will try to funnel financial capital to healthy businesses that have good prospects for repaying the loans, not to firms that are suffering losses and may be unable to repay.

HOW ARE BANKS, SAVINGS AND LOANS, AND CREDIT UNIONS RELATED?

Banks have a couple of close cousins: savings institutions and credit unions. Banks, as we explained, receive deposits from individuals and businesses and make loans with the money. Savings institutions are also sometimes called “savings and loans” or “thrifts.” They also take loans and make deposits. However, from the 1930s until the 1980s, federal law limited how much interest savings institutions were allowed to pay to depositors. They were also required to make most of their loans in the form of housing-related loans, either to homebuyers or to real-estate developers and builders.

A credit union is a nonprofit financial institution that its members own and run. Members of each credit union decide who is eligible to be a member. Usually, potential members would be everyone in a certain community, or groups of employees, or members of a certain organization. The credit union accepts deposits from members and focuses on making loans back to its members. While there are more credit unions than banks and more banks than savings and loans, the total assets of credit unions are growing.

In 2008, there were 7,085 banks. Due to the bank failures of 2007–2009 and bank mergers, there were 5,571 banks in the United States at the end of the fourth quarter in 2014. According to the Credit Union National Association, as of December 2014 there were 6,535 credit unions with assets totaling $1.1 billion. A day of “Transfer Your Money” took place in 2009 out of general public disgust with big bank bailouts. People were encouraged to transfer their deposits to credit unions. This has grown into the ongoing Move Your Money Project. Consequently, some now hold deposits as large as $50 billion. However, as of 2013, the 12 largest banks (0.2%) controlled 69 percent of all banking assets, according to the Dallas Federal Reserve.

15.3.2 A Bank's Balance Sheet

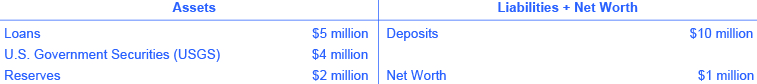

A balance sheet is an accounting tool that lists assets and liabilities. An asset is something of value that you own and you can use to produce something. For example, you can use the cash you own to pay your tuition. If you own a home, this is also an asset. A liability is a debt or something you owe. Many people borrow money to buy homes. In this case, a home is the asset, but the mortgage is the liability. The net worth is the asset value minus how much is owed (the liability). A bank’s balance sheet operates in much the same way. A bank’s net worth as bank capital. We also refer to a bank has assets such as cash held in its vaults, monies that the bank holds at the Federal Reserve bank (called “reserves”), loans that it makes to customers, and bonds.

Figure 15.4 illustrates a hypothetical and simplified balance sheet for the Safe and Secure Bank. Because of the two-column format of the balance sheet, with the T-shape formed by the vertical line down the middle and the horizontal line under “Assets” and “Liabilities,” we sometimes call it a T-account.

The “T” in a T-account separates the assets of a firm, on the left, from its liabilities, on the right. All firms use T-accounts, though most are much more complex. For a bank, the assets are the financial instruments that either the bank is holding (its reserves) or those instruments where other parties owe money to the bank—like loans made by the bank and U.S. Government Securities, such as U.S. treasury bonds purchased by the bank. Liabilities are what the bank owes to others. Specifically, the bank owes any deposits made in the bank to those who have made them. The net worth of the bank is the total assets minus total liabilities. Net worth is included on the liabilities side to have the T account balance to zero. For a healthy business, net worth will be positive. For a bankrupt firm, net worth will be negative. In either case, on a bank’s T-account, assets will always equal liabilities plus net worth.

When bank customers deposit money into a checking account, savings account, or a certificate of deposit, the bank views these deposits as liabilities. After all, the bank owes these deposits to its customers, when the customers wish to withdraw their money. In the example in Figure 15.4, the Safe and Secure Bank holds $10 million in deposits.

Loans are the first category of bank assets in Figure 15.4. Say that a family takes out a 30-year mortgage loan to purchase a house, which means that the borrower will repay the loan over the next 30 years. This loan is clearly an asset from the bank’s perspective, because the borrower has a legal obligation to make payments to the bank over time. However, in practical terms, how can we measure the value of the mortgage loan that the borrower is paying over 30 years in the present? One way of measuring the value of something—whether a loan or anything else—is by estimating what another party in the market is willing to pay for it. Many banks issue home loans, and charge various handling and processing fees for doing so, but then sell the loans to other banks or financial institutions who collect the loan payments. We call the market where financial institutions make loans to borrowers the primary loan market, while the market in which financial institutions buy and sell these loans is the secondary loan market.

One key factor that affects what financial institutions are willing to pay for a loan, when they buy it in the secondary loan market, is the perceived riskiness of the loan: that is, given the borrower's characteristics, such as income level and whether the local economy is performing strongly, what proportion of loans of this type will the borrower repay? The greater the risk that a borrower will not repay loan, the less that any financial institution will pay to acquire the loan. Another key factor is to compare the interest rate the financial institution charged on the original loan with the current interest rate in the economy. If the original loan requires the borrower to pay a low interest rate, but current interest rates are relatively high, then a financial institution will pay less to acquire the loan. In contrast, if the original loan requires the borrower to pay a high interest rate, while current interest rates are relatively low, then a financial institution will pay more to acquire the loan. For the Safe and Secure Bank in this example, the total value of its loans if they sold them to other financial institutions in the secondary market is $5 million.

The second category of bank asset is bonds, which are a common mechanism for borrowing, used by the federal and local government, and also private companies, and nonprofit organizations. A bank takes some of the money it has received in deposits and uses the money to buy bonds—typically bonds issued that the U.S. government issues. Government bonds are low-risk because the government is virtually certain to pay off the bond, albeit at a low rate of interest. These bonds are an asset for banks in the same way that loans are an asset: The bank will receive a stream of payments in the future. In our example, the Safe and Secure Bank holds bonds worth a total value of $4 million.

The final entry under assets is reserves, which is money that the bank keeps on hand, and that it does not lend or invest in bonds—and thus does not lead to interest payments. The Federal Reserve requires that banks keep a certain percentage of depositors’ money on “reserve,” which means either in their vaults or at the Federal Reserve Bank. We call this a reserve requirement. (Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation will explain how the level of these required reserves are one policy tool that governments have to influence bank behavior.) Additionally, banks may also want to keep a certain amount of reserves on hand in excess of what is required. The Safe and Secure Bank is holding $2 million in reserves.

We define net worth of a bank as its total assets minus its total liabilities. For the Safe and Secure Bank in Figure 15.4, net worth is equal to $1 million; that is, $11 million in assets minus $10 million in liabilities. For a financially healthy bank, the net worth will be positive. If a bank has negative net worth and depositors tried to withdraw their money, the bank would not be able to give all depositors their money.

15.3.3 How Banks Go Bankrupt

A bank that is bankrupt will have a negative net worth, meaning its assets will be worth less than its liabilities. How can this happen? Again, looking at the balance sheet helps to explain.

A well-run bank will assume that a small percentage of borrowers will not repay their loans on time, or at all, and factor these missing payments into its planning. Remember, the calculations of the banks' expenses every year include a factor for loans that borrowers do not repay, and the value of a bank’s loans on its balance sheet assumes a certain level of riskiness because some customers will not repay loans. Even if a bank expects a certain number of loan defaults, it will suffer if the number of loan defaults is much greater than expected, as can happen during a recession. For example, if the Safe and Secure Bank in Figure experienced a wave of unexpected defaults, so that its loans declined in value from $5 million to $3 million, then the assets of the Safe and Secure Bank would decline so that the bank had negative net worth.

WHAT LED TO THE 2008–2009 FINANCIAL CRISIS?

Many banks make mortgage loans so that people can buy a home, but then do not keep the loans on their books as an asset. Instead, the bank sells the loan. These loans are “securitized,” which means that they are bundled together into a financial security that a financial institution sells to investors. Investors in these mortgage-backed securities receive a rate of return based on the level of payments that people make on all the mortgages that stand behind the security.

Securitization offers certain advantages. If a bank makes most of its loans in a local area, then the bank may be financially vulnerable if the local economy declines, so that many people are unable to make their payments. However, if a bank sells its local loans, and then buys a mortgage-backed security based on home loans in many parts of the country, it can avoid exposure to local financial risks. (In the simple example in the text, banks just own “bonds.” In reality, banks can own a number of financial instruments, as long as these financial investments are safe enough to satisfy the government bank regulators.) From the standpoint of a local homebuyer, securitization offers the benefit that a local bank does not need to have significant extra funds to make a loan, because the bank is only planning to hold that loan for a short time, before selling the loan so that it can pool it into a financial security.

However, securitization also offers one potentially large disadvantage. If a bank plans to hold a mortgage loan as an asset, the bank has an incentive to scrutinize the borrower carefully to ensure that the customer is likely to repay the loan. However, a bank that plans to sell the loan may be less careful in making the loan in the first place. The bank will be more willing to make what we call “subprime loans,” which are loans that have characteristics like low or zero down-payment, little scrutiny of whether the borrower has a reliable income, and sometimes low payments for the first year or two that will be followed by much higher payments. Economists dubbed some financial institutions that made subprime loans in the mid-2000s NINJA loans: loans that financial institutions made even though the borrower had demonstrated No Income, No Job, or Assets.

Financial institutions typically sold these subprime loans and turned them into financial securities—but with a twist. The idea was that if losses occurred on these mortgage-backed securities, certain investors would agree to take the first, say, 5% of such losses. Other investors would agree to take, say, the next 5% of losses. By this approach, still other investors would not need to take any losses unless these mortgage-backed financial securities lost 25% or 30% or more of their total value. These complex securities, along with other economic factors, encouraged a large expansion of subprime loans in the mid-2000s.

The economic stage was now set for a banking crisis. Banks thought they were buying only ultra-safe securities, because even though the securities were ultimately backed by risky subprime mortgages, the banks only invested in the part of those securities where they were protected from small or moderate levels of losses. However, as housing prices fell after 2007, and the deepening recession made it harder for many people to make their mortgage payments, many banks found that their mortgage-backed financial assets could be worth much less than they had expected—and so the banks were faced with staring bankruptcy. In the 2008–2011 period, 318 banks failed in the United States.

The risk of an unexpectedly high level of loan defaults can be especially difficult for banks because a bank’s liabilities, namely it customers' deposits. Customers can withdraw funds quickly but many of the bank’s assets like loans and bonds will only be repaid over years or even decades. This asset-liability time mismatch—the ability for customers to withdraw bank’s liabilities in the short term while customers repay its assets in the long term—can cause severe problems for a bank. For example, imagine a bank that has loaned a substantial amount of money at a certain interest rate, but then sees interest rates rise substantially. The bank can find itself in a precarious situation. If it does not raise the interest rate it pays to depositors, then deposits will flow to other institutions that offer the higher interest rates that are now prevailing. However, if the bank raises the interest rates that it pays to depositors, it may end up in a situation where it is paying a higher interest rate to depositors than it is collecting from those past loans that it at lower interest rates. Clearly, the bank cannot survive in the long term if it is paying out more in interest to depositors than it is receiving from borrowers.

How can banks protect themselves against an unexpectedly high rate of loan defaults and against the risk of an asset-liability time mismatch? One strategy is for a bank to diversify its loans, which means lending to a variety of customers. For example, suppose a bank specialized in lending to a niche market—say, making a high proportion of its loans to construction companies that build offices in one downtown area. If that one area suffers an unexpected economic downturn, the bank will suffer large losses. However, if a bank loans both to consumers who are buying homes and cars and also to a wide range of firms in many industries and geographic areas, the bank is less exposed to risk. When a bank diversifies its loans, those categories of borrowers who have an unexpectedly large number of defaults will tend to be balanced out, according to random chance, by other borrowers who have an unexpectedly low number of defaults. Thus, diversification of loans can help banks to keep a positive net worth. However, if a widespread recession occurs that touches many industries and geographic areas, diversification will not help.

Along with diversifying their loans, banks have several other strategies to reduce the risk of an unexpectedly large number of loan defaults. For example, banks can sell some of the loans they make in the secondary loan market, as we described earlier, and instead hold a greater share of assets in the form of government bonds or reserves. Nevertheless, in a lengthy recession, most banks will see their net worth decline because customers will not repay a higher share of loans in tough economic times.

- Banks facilitate using money for transactions in the economy because people and firms can use bank accounts when selling or buying goods and services, when paying a worker or receiving payment, and when saving money or receiving a loan.

- In the financial capital market, banks are financial intermediaries; that is, they operate between savers who supply financial capital and borrowers who demand loans.

- A balance sheet (sometimes called a T-account) is an accounting tool which lists assets in one column and liabilities in another. The bank's liabilities are its deposits. The bank's assets include its loans, its ownership of bonds, and its reserves (which it does not loan out).

- We calculate a bank's net worth by subtracting its liabilities from its assets. Banks run a risk of negative net worth if the value of their assets declines. The value of assets can decline because of an unexpectedly high number of defaults on loans, or if interest rates rise and the bank suffers an asset-liability time mismatch in which the bank is receiving a low interest rate on its long-term loans but must pay the currently higher market interest rate to attract depositors.

- Banks can protect themselves against these risks by choosing to diversify their loans or to hold a greater proportion of their assets in bonds and reserves. If banks hold only a fraction of their deposits as reserves, then the process of banks’ lending money, re-depositing those loans in banks, and the banks making additional loans will create money in the economy.

- Why do we call a bank a financial intermediary?

- What does a balance sheet show?

- What are a bank's assets? What are its liabilities?

- How do you calculate a bank's net worth?

- How can a bank end up with negative net worth?

- What is the asset-liability time mismatch that all banks face?

- What is the risk if a bank does not diversify its loans?

15.4 How Banks Create Money

Banks and money are intertwined. It is not just that most money is in the form of bank accounts. The banking system can literally create money through the process of making loans. Let’s see how.

15.4.1 Money Creation by a Single Bank

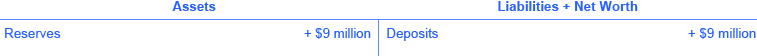

Start with a hypothetical bank called Singleton Bank. The bank has $10 million in deposits. The T-account balance sheet for Singleton Bank, when it holds all of the deposits in its vaults, is in Figure 15.5. At this stage, Singleton Bank is simply storing money for depositors and is using these deposits to make loans. In this simplified example, Singleton Bank cannot earn any interest income from these loans and cannot pay its depositors an interest rate either.

The Federal Reserve requires Singleton Bank to keep $1 million on reserve (10% of total deposits). It will loan out the remaining $9 million. By loaning out the $9 million and charging interest, it will be able to make interest payments to depositors and earn interest income for Singleton Bank (for now, we will keep it simple and not put interest income on the balance sheet). Instead of becoming just a storage place for deposits, Singleton Bank can become a financial intermediary between savers and borrowers.

This change in business plan alters Singleton Bank’s balance sheet, as Figure 15.6 shows. Singleton’s assets have changed. It now has $1 million in reserves and a loan to Hank’s Auto Supply of $9 million. The bank still has $10 million in deposits.

Singleton Bank lends $9 million to Hank’s Auto Supply. The bank records this loan by making an entry on the balance sheet to indicate that it has made a loan. This loan is an asset, because it will generate interest income for the bank. Of course, the loan officer will not allow let Hank to walk out of the bank with $9 million in cash. The bank issues Hank’s Auto Supply a cashier’s check for the $9 million. Hank deposits the loan in his regular checking account with First National. The deposits at First National rise by $9 million and its reserves also rise by $9 million, as Figure 15.7 shows. First National must hold 10% of additional deposits as required reserves but is free to loan out the rest

Making loans that are deposited into a demand deposit account increases the M1 money supply. Remember the definition of M1 includes checkable (demand) deposits, which one can easily use as a medium of exchange to buy goods and services. Notice that the money supply is now $19 million: $10 million in deposits in Singleton bank and $9 million in deposits at First National. Obviously as Hank’s Auto Supply writes checks to pay its bills the deposits will draw down. However, the bigger picture is that a bank must hold enough money in reserves to meet its liabilities. The rest the bank loans out. In this example so far, bank lending has expanded the money supply by $9 million.

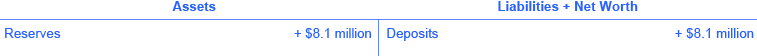

Now, First National must hold only 10% as required reserves ($900,000) but can lend out the other 90% ($8.1 million) in a loan to Jack’s Chevy Dealership as Figure 15.8 shows.

If Jack’s deposits the loan in its checking account at Second National, the money supply just increased by an additional $8.1 million, as Figure 15.9 shows.

How is this money creation possible? It is possible because there are multiple banks in the financial system, they are required to hold only a fraction of their deposits, and loans end up deposited in other banks, which increases deposits and, in essence, the money supply.

15.4.2 The Money Multiplier and a Multi-Bank System

In a system with multiple banks, Singleton Bank deposited the initial excess reserve amount that it decided to lend to Hank’s Auto Supply into First National Bank, which is free to loan out $8.1 million. If all banks loan out their excess reserves, the money supply will expand. In a multi-bank system, institutions determine the amount of money that the system can create by using the money multiplier. This tells us by how many times a loan will be “multiplied” as it is spent in the economy and then re-deposited in other banks.

Fortunately, a formula exists for calculating the total of these many rounds of lending in a banking system. The money multiplier formula is:

\[\frac{1}{Reserve Requirement}\]

We then multiply the money multiplier by the change in excess reserves to determine the total amount of M1 money supply created in the banking system. See the Work it Out feature to walk through the multiplier calculation.

USING THE MONEY MULTIPLIER FORMULA

Using the money multiplier for the example in this text:

- Step 1.

-

In the case of Singleton Bank, for whom the reserve requirement is 10% (or 0.10), the money multiplier is 1 divided by .10, which is equal to 10.

- Step 2.

-

We have identified that the excess reserves are $9 million, so, using the formula we can determine the total change in the M1 money supply:

Total Change in the M1 Money Supply =

\(= \frac{1}{ReserveRequirement} \times Excess Requirement\)

$= 0.10 \(9 million\)

$= 10 \(9 million\)

$= \(90 million\)

- Step 3.

-

Thus, we can say that, in this example, the total quantity of money generated in this economy after all rounds of lending are completed will be $90 million.

15.4.3 Cautions about the Money Multiplier

The money multiplier will depend on the proportion of reserves that the Federal Reserve Band requires banks to hold. Additionally, a bank can also choose to hold extra reserves. Banks may decide to vary how much they hold in reserves for two reasons: macroeconomic conditions and government rules. When an economy is in recession, banks are likely to hold a higher proportion of reserves because they fear that customers are less likely to repay loans when the economy is slow. The Federal Reserve may also raise or lower the required reserves held by banks as a policy move to affect the quantity of money in an economy, as Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation will discuss.

The process of how banks create money shows how the quantity of money in an economy is closely linked to the quantity of lending or credit in the economy. All the money in the economy, except for the original reserves, is a result of bank loans that institutions repeatedly re-deposit and loan.

Finally, the money multiplier depends on people re-depositing the money that they receive in the banking system. If people instead store their cash in safe-deposit boxes or in shoeboxes hidden in their closets, then banks cannot recirculate the money in the form of loans. Central banks have an incentive to assure that bank deposits are safe because if people worry that they may lose their bank deposits, they may start holding more money in cash, instead of depositing it in banks, and the quantity of loans in an economy will decline. Low-income countries have what economists sometimes refer to as “mattress savings,” or money that people are hiding in their homes because they do not trust banks. When mattress savings in an economy are substantial, banks cannot lend out those funds and the money multiplier cannot operate as effectively. The overall quantity of money and loans in such an economy will decline.

15.4.4 Money and Banks—Benefits and Dangers

Money and banks are marvelous social inventions that help a modern economy to function. Compared with the alternative of barter, money makes market exchanges vastly easier in goods, labor, and financial markets. Banking makes money still more effective in facilitating exchanges in goods and labor markets. Moreover, the process of banks making loans in financial capital markets is intimately tied to the creation of money.

However, the extraordinary economic gains that are possible through money and banking also suggest some possible corresponding dangers. If banks are not working well, it sets off a decline in convenience and safety of transactions throughout the economy. If the banks are under financial stress, because of a widespread decline in the value of their assets, loans may become far less available, which can deal a crushing blow to sectors of the economy that depend on borrowed money like business investment, home construction, and car manufacturing. The 2008–2009 Great Recession illustrated this pattern.

THE MANY DISGUISES OF MONEY: FROM COWRIES TO BIT COINS

The global economy has come a long way since it started using cowrie shells as currency. We have moved away from commodity and commodity-backed paper money to fiat currency. As technology and global integration increases, the need for paper currency is diminishing, too. Every day, we witness the increased use of debit and credit cards.

The latest creation and perhaps one of the purest forms of fiat money is the Bitcoin. Bitcoins are a digital currency that allows users to buy goods and services online. Customers can purchase products and services such as videos and books using Bitcoins. This currency is not backed by any commodity nor has any government decreed as legal tender, yet customers use it as a medium of exchange and can store its value (online at least). It is also unregulated by any central bank, but is created online through people solving very complicated mathematics problems and receiving payment afterward. Bitcoin.org is an information source if you are curious. Bitcoins are a relatively new type of money. At present, because it is not sanctioned as a legal currency by any country nor regulated by any central bank, it lends itself for use in illegal as well as legal trading activities. As technology increases and the need to reduce transactions costs associated with using traditional forms of money increases, Bitcoins or some sort of digital currency may replace our dollar bill, just as man replaced the cowrie shell.

We define the money multiplier as the quantity of money that the banking system can generate from each $1 of bank reserves. The formula for calculating the multiplier is 1/reserve ratio, where the reserve ratio is the fraction of deposits that the bank wishes to hold as reserves. The quantity of money in an economy and the quantity of credit for loans are inextricably intertwined. The network of banks making loans, people making deposits, and banks making more loans creates much of the money in an economy.

Given the macroeconomic dangers of a malfunctioning banking system, Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation will discuss government policies for controlling the money supply and for keeping the banking system safe.

- Imagine that you are in the position of buying loans in the secondary market (that is, buying the right to collect the payments on loans) for a bank or other financial services company. Explain why you would be willing to pay more or less for a given loan if:

- The borrower has been late on a number of loan payments

- Interest rates in the economy as a whole have risen since the bank made the loan

- The borrower is a firm that has just declared a high level of profits

- Interest rates in the economy as a whole have fallen since the bank made the loan

- How do banks create money?

- What is the formula for the money multiplier?

- Should banks have to hold 100% of their deposits? Why or why not?

- Explain what will happen to the money multiplier process if there is an increase in the reserve requirement?

- What do you think the Federal Reserve Bank did to the reserve requirement during the 2008–2009 Great Recession?

15.5 The Federal Reserve Banking System and Central Banks

In making decisions about the money supply, a central bank decides whether to raise or lower interest rates and, in this way, to influence macroeconomic policy, whose goal is low unemployment and low inflation. The central bank is also responsible for regulating all or part of the nation’s banking system to protect bank depositors and insure the health of the bank’s balance sheet.

We call the organization responsible for conducting monetary policy and ensuring that a nation’s financial system operates smoothly the central bank. Most nations have central banks or currency boards. Some prominent central banks around the world include the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the Bank of England. In the United States, we call the central bank the Federal Reserve—often abbreviated as just “the Fed.” This section explains the U.S. Federal Reserve's organization and identifies the major central bank's responsibilities.

15.5.1 Structure/Organization of the Federal Reserve

Unlike most central banks, the Federal Reserve is semi-decentralized, mixing government appointees with representation from private-sector banks. At the national level, it is run by a Board of Governors, consisting of seven members appointed by the President of the United States and confirmed by the Senate. Appointments are for 14-year terms and they are arranged so that one term expires January 31 of every even-numbered year. The purpose of the long and staggered terms is to insulate the Board of Governors as much as possible from political pressure so that governors can make policy decisions based only on their economic merits. Additionally, except when filling an unfinished term, each member only serves one term, further insulating decision-making from politics. The Fed's policy decisions do not require congressional approval, and the President cannot ask for a Federal Reserve Governor to resign as the President can with cabinet positions.

One member of the Board of Governors is designated as the Chair. For example, from 1987 until early 2006, the Chair was Alan Greenspan. From 2006 until 2014, Ben Bernanke held the post. The current Chair, Janet Yellen, has made many headlines already. Why? See the following Clear It Up feature to find out.

WHO HAS THE MOST IMMEDIATE ECONOMIC POWER IN THE WORLD?

Chair of the Federal Reserve Board

This image is a photograph of Janet Yellen.

What individual can make financial market crash or soar just by making a public statement? It is not Bill Gates or Warren Buffett. It is not even the President of the United States. The answer is the Chair of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. In early 2014, Janet L. Yellen, (Figure) became the first woman to hold this post. The media had described Yellen as “perhaps the most qualified Fed chair in history.”

With a Ph.D. in economics from Yale University, Yellen has taught macroeconomics at Harvard, the London School of Economics, and most recently at the University of California at Berkeley.

From 2004–2010, Yellen was President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Not an ivory tower economist, Yellen became one of the few economists who warned about a possible bubble in the housing market, more than two years before the financial crisis occurred.

Yellen served on the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve twice, most recently as Vice Chair. She also spent two years as Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors. If experience and credentials mean anything, Yellen is likely to be an effective Fed chair.

The new Chair of the FED.

This is an image of the swearing in ceremony of Jerome H. Powell, the new chair of the FED who was appointed by Trump in 2018.

Jerome H. Powell took office as Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System on February 5, 2018, for a four-year term. Mr. Powell also serves as Chairman of the Federal Open Market Committee, the System's principal monetary policymaking body. Mr. Powell has served as a member of the Board of Governors since taking office on May 25, 2012, to fill an unexpired term. He was reappointed to the Board and sworn in on June 16, 2014, for a term ending January 31, 2028.

Prior to his appointment to the Board, Mr. Powell was a visiting scholar at the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington, D.C., where he focused on federal and state fiscal issues. From 1997 through 2005, Mr. Powell was a partner at The Carlyle Group.

Mr. Powell served as an Assistant Secretary and as Undersecretary of the Treasury under President George H.W. Bush, with responsibility for policy on financial institutions, the Treasury debt market, and related areas. Prior to joining the Administration, he worked as a lawyer and investment banker in New York City.

In addition to service on corporate boards, Mr. Powell has served on the boards of charitable and educational institutions, including the Bendheim Center for Finance at Princeton University and The Nature Conservancy of Washington, D.C., and Maryland.

Mr. Powell was born in February 1953 in Washington, D.C. He received an AB in politics from Princeton University in 1975 and earned a law degree from Georgetown University in 1979. While at Georgetown, he was editor-in-chief of the Georgetown Law Journal.

Source of biography: www.federalreserve.gov

The Fed Chair is first among equals on the Board of Governors. While he or she has only one vote, the Chair controls the agenda, and is the Fed's public voice, so he or she has more power and influence than one might expect.

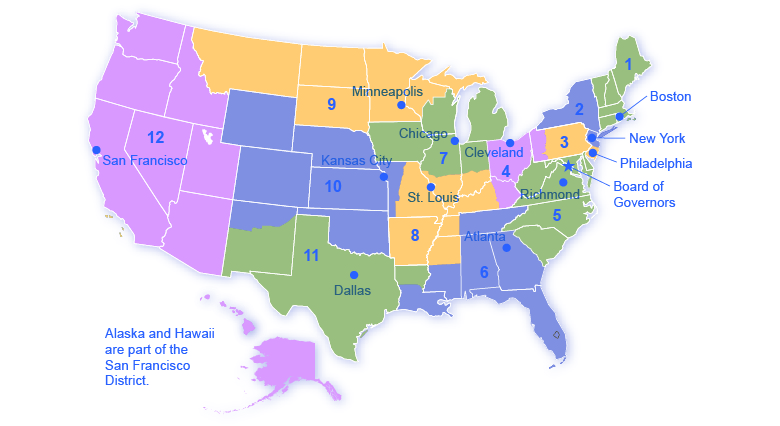

The Federal Reserve is more than the Board of Governors. The Fed also includes 12 regional Federal Reserve banks, each of which is responsible for supporting the commercial banks and economy generally in its district. Figure 15.12 shows the Federal Reserve districts and the cities where their regional headquarters are located. The commercial banks in each district elect a Board of Directors for each regional Federal Reserve bank, and that board chooses a president for each regional Federal Reserve district. Thus, the Federal Reserve System includes both federally and private-sector appointed leaders.

15.5.2 Central Bank's Balance Sheet

The central bank's balance sheet shows three basic assets:

- securities (mostly treasury securities that it gets through open market operations)

- foreign exchange reserves (typically bonds issued by foreign governments), and

- loans (such as discount loans to meet banks' short-term cash needs).

The first two are needed so that the central bank can perform its function as a government bank and the second are a service to commercial banks.

| Assets | Liabilities | |

| Government's Bank | Securities | Currency |

| Foreign exchange reserves | Government's account | |

| Banker's Bank | Loans | Accounts of commercial banks (reserves) |

On the liabilities side we have:

- Currency

- Government's account (gov't deposits tax revenue funds)

- Commercial bank accounts (reserves)

The last one, reserves, are the sum of two parts: (i) deposits at the central bank plus (ii) the cash in the commercial bank's own vault. A commercial bank holds reserves for two reasons. First, it has to hold required reserves and second it holds voluntary reserves that are called excess reserves.

15.5.3 What Does a Central Bank Do?

The Federal Reserve, like most central banks, is designed to perform three important functions:

- To conduct monetary policy

- To promote stability of the financial system

- To provide banking services to commercial banks and other depository institutions, and to provide banking services to the federal government.

The first two functions are sufficiently important that we will discuss them in their own modules. The third function we will discuss here.

The Federal Reserve provides many of the same services to banks as banks provide to their customers. For example, all commercial banks have an account at the Fed where they deposit reserves. Similarly, banks can obtain loans from the Fed through the “discount window” facility, which we will discuss in more detail later. The Fed is also responsible for check processing. When you write a check, for example, to buy groceries, the grocery store deposits the check in its bank account. Then, the grocery store's bank returns the physical check (or an image of that actual check) to your bank, after which it transfers funds from your bank account to the grocery store's account. The Fed is responsible for each of these actions.

On a more mundane level, the Federal Reserve ensures that enough currency and coins are circulating through the financial system to meet public demands. For example, each year the Fed increases the amount of currency available in banks around the Christmas shopping season and reduces it again in January.

Finally, the Fed is responsible for assuring that banks are in compliance with a wide variety of consumer protection laws. For example, banks are forbidden from discriminating on the basis of age, race, sex, or marital status. Banks are also required to disclose publicly information about the loans they make for buying houses and how they distribute the loans geographically, as well as by sex and race of the loan applicants.

- The most prominent task of a central bank is to conduct monetary policy, which involves changes to interest rates and credit conditions, affecting the amount of borrowing and spending in an economy.

- Some prominent central banks around the world include the U.S. Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the Bank of England.

- Why is it important for the members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve to have longer terms in office than elected officials, like the President?

- How is a central bank different from a typical commercial bank?

- List the three traditional tools that a central bank has for controlling the money supply.

15.6 Bank Regulation

A safe and stable national financial system is a critical concern of the Federal Reserve. The goal is not only to protect individuals’ savings, but to protect the integrity of the financial system itself. This esoteric task is usually behind the scenes, but came into view during the 2008–2009 financial crisis, when for a brief period of time, critical parts of the financial system failed and firms became unable to obtain financing for ordinary parts of their business. Imagine if suddenly you were unable to access the money in your bank accounts because your checks were not accepted for payment and your debit cards were declined. This gives an idea of a failure of the payments/financial system.

Bank regulation is intended to maintain banks' solvency by avoiding excessive risk. Regulation falls into a number of categories, including reserve requirements, capital requirements, and restrictions on the types of investments banks may make. In Money and Banking, we learned that banks are required to hold a minimum percentage of their deposits on hand as reserves. “On hand” is a bit of a misnomer because, while a portion of bank reserves are held as cash in the bank, the majority are held in the bank’s account at the Federal Reserve, and their purpose is to cover desired withdrawals by depositors. Another part of bank regulation is restrictions on the types of investments banks are allowed to make. Banks are permitted to make loans to businesses, individuals, and other banks. They can purchase U.S. Treasury securities but, to protect depositors, they are not permitted to invest in the stock market or other assets that are perceived as too risky.

Bank capital is the difference between a bank’s assets and its liabilities. In other words, it is a bank’s net worth. A bank must have positive net worth; otherwise it is insolvent or bankrupt, meaning it would not have enough assets to pay back its liabilities. Regulation requires that banks maintain a minimum net worth, usually expressed as a percent of their assets, to protect their depositors and other creditors.

15.6.1 Bank Supervision

Several government agencies monitor banks' balance sheets to make sure they have positive net worth and are not taking too high a level of risk. Within the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency has a national staff of bank examiners who conduct on-site reviews of the 1,500 or so of the largest national banks. The bank examiners also review any foreign banks that have branches in the United States. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency also monitors and regulates about 800 savings and loan institutions.

The National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) supervises credit unions, which are nonprofit banks that their members run and own. There are over 6,000 credit unions in the U.S. economy, although the typical credit union is small compared to most banks.

The Federal Reserve also has some responsibility for supervising financial institutions. For example, we call conglomerate firms that own banks and other businesses “bank holding companies.” While other regulators like the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency supervises the banks, the Federal Reserve supervises the holding companies.

When bank supervision (and bank-like institutions such as savings and loans and credit unions) works well, most banks will remain financially healthy most of the time. If the bank supervisors find that a bank has low or negative net worth, or is making too high a proportion of risky loans, they can require that the bank change its behavior—or, in extreme cases, even force the bank to close or be sold to a financially healthy bank.

Bank supervision can run into both practical and political questions. The practical question is that measuring the value of a bank’s assets is not always straightforward. As we discussed in Money and Banking, a bank’s assets are its loans, and the value of these assets depends on estimates about the risk that customers will not repay these loans. These issues can become even more complex when a bank makes loans to banks or firms in other countries, or arranges financial deals that are much more complex than a basic loan.

The political question arises because a bank supervisor's decision to require a bank to close or to change its financial investments is often controversial, and the bank supervisor often comes under political pressure from the bank's owners and the local politicians to keep quiet and back off.

For example, many observers have pointed out that Japan’s banks were in deep financial trouble through most of the 1990s; however, nothing substantial had been done about it by the early 2000s. A similar unwillingness to confront problems with struggling banks is visible across the rest of the world, in East Asia, Latin America, Eastern Europe, Russia, and elsewhere.

In the United States, the government passed laws in the 1990s requiring that bank supervisors make their findings open and public, and that they act as soon as they identify a problem. However, as many U.S. banks were staggered by the 2008-2009 recession, critics of the bank regulators asked pointed questions about why the regulators had not foreseen the banks' financial shakiness earlier, before such large losses had a chance to accumulate.

15.6.2 Bank Runs

Back in the nineteenth century and during the first few decades of the twentieth century (around and during the Great Depression), putting your money in a bank could be nerve-wracking. Imagine that the net worth of your bank became negative, so that the bank’s assets were not enough to cover its liabilities. In this situation, whoever withdrew their deposits first received all of their money, and those who did not rush to the bank quickly enough, lost their money. We call depositors racing to the bank to withdraw their deposits, as Figure 15.13 shows a bank run. In the movie It’s a Wonderful Life, the bank manager, played by Jimmy Stewart, faces a mob of worried bank depositors who want to withdraw their money, but manages to allay their fears by allowing some of them to withdraw a portion of their deposits—using the money from his own pocket that was supposed to pay for his honeymoon.

The risk of bank runs created instability in the banking system. Even a rumor that a bank might experience negative net worth could trigger a bank run and, in a bank run, even healthy banks could be destroyed. Because a bank loans out most of the money it receives, and because it keeps only limited reserves on hand, a bank run of any size would quickly drain any of the bank’s available cash. When the bank had no cash remaining, it only intensified the fears of remaining depositors that they could lose their money. Moreover, a bank run at one bank often triggered a chain reaction of runs on other banks. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, bank runs were typically not the original cause of a recession—but they could make a recession much worse.

15.6.3 Lender of Last Resort

The problem with bank runs is not that insolvent banks will fail; they are, after all, bankrupt and need to be shut down. The problem is that bank runs can cause solvent banks to fail and spread to the rest of the financial system. To prevent this, the Fed stands ready to lend to banks and other financial institutions when they cannot obtain funds from anywhere else. This is known as the lender of last resort role. For banks, the central bank acting as a lender of last resort helps to reinforce the effect of deposit insurance and to reassure bank customers that they will not lose their money.

The lender of last resort task can arise in other financial crises, as well. During the 1987 stock market crash panic, when U.S. stock values fell by 25% in a single day, the Federal Reserve made a number of short-term emergency loans so that the financial system could keep functioning. During the 2008-2009 recession, we can interpret the Fed's “quantitative easing” policies (discussed below) as a willingness to make short-term credit available as needed in a time when the banking and financial system was under stress.

When the central bank lends funds to the commercial bank at the discount rate, then for the borrowing bank this loan is a liability that is matched by an offsetting increase in the level of its reserve account. For the Fed, the loan is an asset that is created in exchange for a credit to the borrower's reserve account. The extension of credit to the banking system raises the level of reserves and expands the monetary base.

- A bank run occurs when there are rumors (possibly true, possibly false) that a bank is at financial risk of having negative net worth. As a result, depositors rush to the bank to withdraw their money and put it someplace safer. Even false rumors, if they cause a bank run, can force a healthy bank to lose its deposits and be forced to close. Deposit insurance guarantees bank depositors that, even if the bank has negative net worth, their deposits will be protected. In the United States, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) collects deposit insurance premiums from banks and guarantees bank deposits up to $250,000. Bank supervision involves inspecting the balance sheets of banks to make sure that they have positive net worth and that their assets are not too risky. In the United States, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) is responsible for supervising banks and inspecting savings and loans and the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) is responsible for inspecting credit unions. The FDIC and the Federal Reserve also play a role in bank supervision.

- When a central bank acts as a lender of last resort, it makes short-term loans available in situations of severe financial panic or stress. The failure of a single bank can be treated like any other business failure. Yet if many banks fail, it can reduce aggregate demand in a way that can bring on or deepen a recession. The combination of deposit insurance, bank supervision, and lender of last resort policies help to prevent weaknesses in the banking system from causing recessions.

Given the danger of bank runs, why do banks not keep the majority of deposits on hand to meet the demands of depositors?

Bank runs are often described as “self-fulfilling prophecies.” Why is this phrase appropriate to bank runs?

How is bank regulation linked to the conduct of monetary policy?

What is a bank run?

In a program of deposit insurance as it is operated in the United States, what is being insured and who pays the insurance premiums?

In government programs of bank supervision, what is being supervised?

What is the lender of last resort?

Name and briefly describe the responsibilities of each of the following agencies: FDIC, NCUA, and OCC.