4. Intro Macro Perspective¶

Macroeconomics focuses on the economy as a whole (or on whole economies as they interact). What causes recessions? What makes unemployment stay high when recessions are supposed to be over? Why do some countries grow faster than others? Why do some countries have higher standards of living than others? These are all questions that macroeconomics addresses. Macroeconomics involves adding up the economic activity of all households and all businesses in all markets to get the overall demand and supply in the economy. However, when we do that, something curious happens. It is not unusual that what results at the macro level is different from the sum of the microeconomic parts. Indeed, what seems sensible from a microeconomic point of view can have unexpected or counterproductive results at the macroeconomic level. Imagine that you are sitting at an event with a large audience, like a live concert or a basketball game. A few people decide that they want a better view, and so they stand up. However, when these people stand up, they block the view for other people, and the others need to stand up as well if they wish to see. Eventually, nearly everyone is standing up, and as a result, no one can see much better than before. The rational decision of some individuals at the micro level—to stand up for a better view—ended up being self-defeating at the macro level. This is not macroeconomics, but it is an apt analogy.

Macroeconomics is a rather massive subject. How are we going to tackle it?

We will study macroeconomics from three different perspectives:

- What are the macroeconomic goals? (Macroeconomics as a discipline does not have goals, but we do have goals for the macro economy.)

- What are the frameworks economists can use to analyze the macroeconomy?

- Finally, what are the policy tools governments can use to manage the macroeconomy?

Goals

In thinking about the overall health of the macroeconomy, it is useful to consider three primary goals: economic growth, low unemployment, and low inflation.

- Economic growth ultimately determines the prevailing standard of living in a country. Economic growth is measured by the percentage change in real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product. A growth rate of more than 3% is considered good.

- Unemployment, as measured by the unemployment rate, is the percentage of people in the labor force who do not have a job. When people lack jobs, the economy is wasting a precious resource-labor, and the result is

Frameworks

As you learn in the micro part of this book, principal tools used by economists are theories and models (see Welcome to Economics! for more on this). In microeconomics, we used the theories of supply and demand; in macroeconomics, we use the theories of aggregate demand (AD) and aggregate supply (AS). This book presents two perspectives on macroeconomics: the Neoclassical perspective and the Keynesian perspective, each of which has its own version of AD and AS. Between the two perspectives, you will obtain a good understanding of what drives the macroeconomy.

Policy Tools

National governments have two tools for influencing the macroeconomy. The first is monetary policy, which involves managing the money supply and interest rates. The second is fiscal policy, which involves changes in government spending/purchases and taxes. Each of the items in Figure will be explained in detail in one or more other chapters. As you learn these things, you will discover that the goals and the policy tools are in the news almost every day.

4.1. Measuring the Size of the Economy: Gross Domestic Product¶

Macroeconomics is an empirical subject, so the first step toward understanding it is to measure the economy. How large is the U.S. economy? The size of a nation’s overall economy is typically measured by its gross domestic product (GDP), which is the value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given year. The measurement of GDP involves counting up the production of millions of different goods and services—smart phones, cars, music downloads, computers, steel, bananas, college educations, and all other new goods and services produced in the current year—and summing them into a total dollar value. This task is straightforward: take the quantity of everything produced, multiply it by the price at which each product sold, and add up the total. In 2014, the U.S. GDP totaled $17.4 trillion, the largest GDP in the world. Each of the market transactions that enter into GDP must involve both a buyer and a seller. The GDP of an economy can be measured either by the total dollar value of what is purchased in the economy, or by the total dollar value of what is produced. There is even a third way, as we will explain later.

4.1.1. GDP Measured by Components of Demand¶

Who buys all of this production? This demand can be divided into four main parts: consumer spending (consumption), business spending (investment), government spending on goods and services, and spending on net exports. (See the following Clear It Up feature to understand what is meant by investment.)

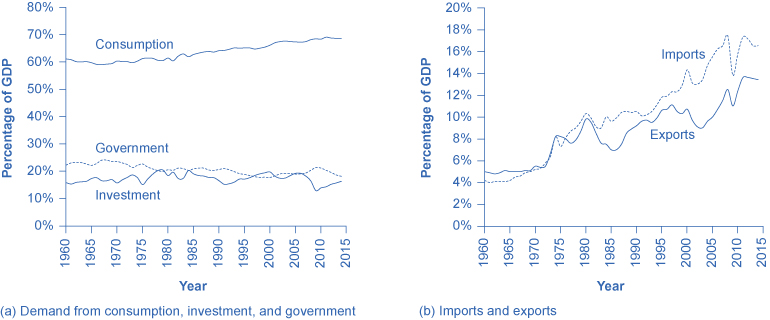

Table 4.1 shows how these four components added up to the GDP in 2014. Fig. 4.1 Panel (a) shows the levels of consumption, investment, and government purchases over time, expressed as a percentage of GDP, while Fig. 4.1 Panel (b) shows the levels of exports and imports as a percentage of GDP over time. A few patterns about each of these components are worth noticing. Table shows the components of GDP from the demand side.

| Component | Trillions of $ | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Consumption | $11.9 | 68.4% |

| Investment | $2.9 | 16.7% |

| Government | $3.2 | 18.4% |

| Exports | $2.3 | 13.2% |

| Imports | –$2.9 | –16.7% |

| Total GDP | $17.4 | 100% |

Note

WHAT IS MEANT BY THE WORD “INVESTMENT”?

What do economists mean by investment, or business spending? In calculating GDP, investment does not refer to the purchase of stocks and bonds or the trading of financial assets. It refers to the purchase of new capital goods, that is, new commercial real estate (such as buildings, factories, and stores) and equipment, residential housing construction, and inventories. Inventories that are produced this year are included in this year’s GDP—even if they have not yet sold. From the accountant’s perspective, it is as if the firm invested in its own inventories. Business investment in 2014 was almost $3 trillion, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Fig. 4.1 GDP Components on the Demand Side

Consumption expenditure by households is the largest component of GDP, accounting for about two-thirds of the GDP in any year. This tells us that consumers’ spending decisions are a major driver of the economy. However, consumer spending is a gentle elephant: when viewed over time, it does not jump around too much.

Investment expenditure refers to purchases of physical plant and equipment, primarily by businesses. If Starbucks builds a new store, or Amazon buys robots, these expenditures are counted under business investment. Investment demand is far smaller than consumption demand, typically accounting for only about 15–18% of GDP, but it is very important for the economy because this is where jobs are created. However, it fluctuates more noticeably than consumption. Business investment is volatile; new technology or a new product can spur business investment, but then confidence can drop and business investment can pull back sharply.

If you have noticed any of the infrastructure projects (new bridges, highways, airports) launched during the recession of 2009, you have seen how important government spending can be for the economy. Government expenditure in the United States is about 20% of GDP, and includes spending by all three levels of government: federal, state, and local. The only part of government spending counted in demand is government purchases of goods or services produced in the economy. Examples include the government buying a new fighter jet for the Air Force (federal government spending), building a new highway (state government spending), or a new school (local government spending). A significant portion of government budgets are transfer payments, like unemployment benefits, veteran’s benefits, and Social Security payments to retirees. These payments are excluded from GDP because the government does not receive a new good or service in return or exchange. Instead they are transfers of income from taxpayers to others. If you are curious about the awesome undertaking of adding up GDP, read the following Clear It Up feature.

See also

HOW DO STATISTICIANS MEASURE GDP?

Government economists at the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), within the U.S. Department of Commerce, piece together estimates of GDP from a variety of sources.

Once every five years, in the second and seventh year of each decade, the Bureau of the Census carries out a detailed census of businesses throughout the United States. In between, the Census Bureau carries out a monthly survey of retail sales. These figures are adjusted with foreign trade data to account for exports that are produced in the United States and sold abroad and for imports that are produced abroad and sold here. Once every ten years, the Census Bureau conducts a comprehensive survey of housing and residential finance. Together, these sources provide the main basis for figuring out what is produced for consumers.

For investment, the Census Bureau carries out a monthly survey of construction and an annual survey of expenditures on physical capital equipment.

For what is purchased by the federal government, the statisticians rely on the U.S. Department of the Treasury. An annual Census of Governments gathers information on state and local governments. Because a lot of government spending at all levels involves hiring people to provide services, a large portion of government spending is also tracked through payroll records collected by state governments and by the Social Security Administration.

With regard to foreign trade, the Census Bureau compiles a monthly record of all import and export documents. Additional surveys cover transportation and travel, and adjustment is made for financial services that are produced in the United States for foreign customers.

Many other sources contribute to the estimates of GDP. Information on energy comes from the U.S. Department of Transportation and Department of Energy. Information on healthcare is collected by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Surveys of landlords find out about rental income. The Department of Agriculture collects statistics on farming.

All of these bits and pieces of information arrive in different forms, at different time intervals. The BEA melds them together to produce estimates of GDP on a quarterly basis (every three months). These numbers are then “annualized” by multiplying by four. As more information comes in, these estimates are updated and revised. The “advance” estimate of GDP for a certain quarter is released one month after a quarter. The “preliminary” estimate comes out one month after that. The “final” estimate is published one month later, but it is not actually final. In July, roughly updated estimates for the previous calendar year are released. Then, once every five years, after the results of the latest detailed five-year business census have been processed, the BEA revises all of the past estimates of GDP according to the newest methods and data, going all the way back to 1929.

When thinking about the demand for domestically produced goods in a global economy, it is important to count spending on exports—domestically produced goods that are sold abroad. By the same token, we must also subtract spending on imports—goods produced in other countries that are purchased by residents of this country. The net export component of GDP is equal to the dollar value of exports (X) minus the dollar value of imports (M), (X – M). The gap between exports and imports is called the trade balance. If a country’s exports are larger than its imports, then a country is said to have a trade surplus. In the United States, exports typically exceeded imports in the 1960s and 1970s, as shown in Figure (b).

Since the early 1980s, imports have typically exceeded exports, and so the United States has experienced a trade deficit in most years. Indeed, the trade deficit grew quite large in the late 1990s and in the mid-2000s. Figure (b) also shows that imports and exports have both risen substantially in recent decades, even after the declines during the Great Recession between 2008 and 2009. As noted before, if exports and imports are equal, foreign trade has no effect on total GDP. However, even if exports and imports are balanced overall, foreign trade might still have powerful effects on particular industries and workers by causing nations to shift workers and physical capital investment toward one industry rather than another.

Based on these four components of demand, GDP can be measured as:

Understanding how to measure GDP is important for analyzing connections in the macro economy and for thinking about macroeconomic policy tools.

4.1.2. GDP Measured by What is Produced¶

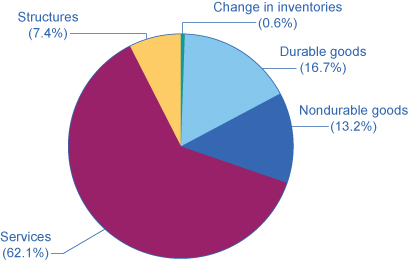

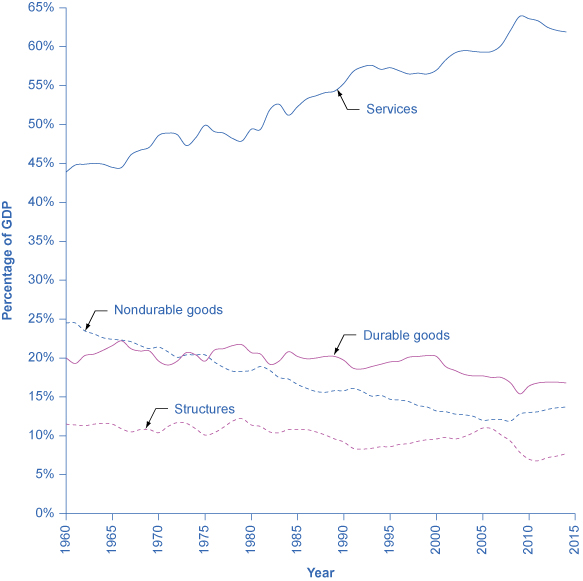

Everything that is purchased must be produced first. Table 4.2 breaks down what is produced into five categories: durable goods, nondurable goods, services, structures, and the change in inventories. Before going into detail about these categories, notice that total GDP measured according to what is produced is exactly the same as the GDP measured by looking at the five components of demand. Fig. 4.2 provides a visual representation of this information.

| Component of GDP | Trillions of $ | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Durable goods | $2.9 | 16.7% |

| Nondurable goods | $2.3 | 13.2% |

| Services | $10.8 | 62.1% |

| Structures | $1.3 | 7.4% |

| Change in inventories | $0.1 | 0.6% |

| Total GDP | $17.4 | 100% |

Fig. 4.2 Services make up over half of the production side components of GDP in the United States.

Since every market transaction must have both a buyer and a seller, GDP must be the same whether measured by what is demanded or by what is produced. Fig. 4.3 shows these components of what is produced, expressed as a percentage of GDP, since 1960.

Fig. 4.3 Services are the largest single component of total supply, representing over half of GDP. Nondurable goods used to be larger than durable goods, but in recent years, nondurable goods have been dropping closer to durable goods, which is about 20% of GDP. Structures hover around 10% of GDP. The change in inventories, the final component of aggregate supply, is not shown here; it is typically less than 1% of GDP.

In thinking about what is produced in the economy, many non-economists immediately focus on solid, long-lasting goods, like cars and computers. By far the largest part of GDP, however, is services. Moreover, services have been a growing share of GDP over time. A detailed breakdown of the leading service industries would include healthcare, education, and legal and financial services. It has been decades since most of the U.S. economy involved making solid objects. Instead, the most common jobs in a modern economy involve a worker looking at pieces of paper or a computer screen; meeting with co-workers, customers, or suppliers; or making phone calls.

Even within the overall category of goods, long-lasting durable goods like cars and refrigerators are about the same share of the economy as short-lived nondurable goods like food and clothing. The category of structures includes everything from homes, to office buildings, shopping malls, and factories. Inventories is a small category that refers to the goods that have been produced by one business but have not yet been sold to consumers, and are still sitting in warehouses and on shelves. The amount of inventories sitting on shelves tends to decline if business is better than expected, or to rise if business is worse than expected.

4.1.3. The Problem of Double Counting¶

GDP is defined as the current value of all final goods and services produced in a nation in a year. What are final goods? They are goods at the furthest stage of production at the end of a year. Statisticians who calculate GDP must avoid the mistake of double counting, in which output is counted more than once as it travels through the stages of production. For example, imagine what would happen if government statisticians first counted the value of tires produced by a tire manufacturer, and then counted the value of a new truck sold by an automaker that contains those tires. In this example, the value of the tires would have been counted twice-because the price of the truck includes the value of the tires.

To avoid this problem, which would overstate the size of the economy considerably, government statisticians count just the value of final goods and services in the chain of production that are sold for consumption, investment, government, and trade purposes. Intermediate goods, which are goods that go into the production of other goods, are excluded from GDP calculations. From the example above, only the value of the Ford truck will be counted. The value of what businesses provide to other businesses is captured in the final products at the end of the production chain.

The concept of GDP is fairly straightforward: it is just the dollar value of all final goods and services produced in the economy in a year. In our decentralized, market-oriented economy, actually calculating the more than $16 trillion-dollar U.S. GDP—along with how it is changing every few months—is a full-time job for a brigade of government statisticians.

| What is Counted in GDP | What is not included in GDP |

|---|---|

| Consumption | Intermediate goods |

| Business investment | Transfer payments and non-market activities |

| Government spending on goods and services | Used goods |

| Net exports | Illegal goods Household production |

Notice the items that are not counted into GDP, as outlined in

tab_CounteingInGDP. The sales of used goods are not included because they were produced in a previous year and are part of that year’s GDP. The entire underground economy of services paid “under the table” and illegal sales should be counted, but is not, because it is impossible to track these sales. In a recent study by Friedrich Schneider of shadow economies, the underground economy in the United States was estimated to be 6.6% of GDP, or close to $2 trillion dollars in 2013 alone. Transfer payments, such as payment by the government to individuals, are not included, because they do not represent production. Also, production of some goods—such as home production as when you make your breakfast—is not counted because these goods are not sold in the marketplace.

4.1.4. Other Ways to Measure the Economy¶

Besides GDP, there are several different but closely related ways of measuring the size of the economy. We mentioned above that GDP can be thought of as total production and as total purchases. It can also be thought of as total income since anything produced and sold produces income.

One of the closest cousins of GDP is the gross national product (GNP). GDP includes only what is produced within a country’s borders. GNP adds what is produced by domestic businesses and labor abroad, and subtracts out any payments sent home to other countries by foreign labor and businesses located in the United States. In other words, GNP is based more on the production of citizens and firms of a country, wherever they are located, and GDP is based on what happens within the geographic boundaries of a certain country. For the United States, the gap between GDP and GNP is relatively small; in recent years, only about 0.2%. For small nations, which may have a substantial share of their population working abroad and sending money back home, the difference can be substantial.

Net national product (NNP) is calculated by taking GNP and then subtracting the value of how much physical capital is worn out, or reduced in value because of aging, over the course of a year. The process by which capital ages and loses value is called depreciation. The NNP can be further subdivided into national income, which includes all income to businesses and individuals, and personal income, which includes only income to people.

For practical purposes, it is not vital to memorize these definitions. However, it is important to be aware that these differences exist and to know what statistic you are looking at, so that you do not accidentally compare, say, GDP in one year or for one country with GNP or NNP in another year or another country. To get an idea of how these calculations work, follow the steps in the following Work It Out feature.

Todo

CALCULATING GDP, NET EXPORTS, AND NNP

- Based on the information in Table 4.4:

- What is the value of GDP?

- What is the value of net exports?

- What is the value of NNP?

| Item | Amount |

|---|---|

| Government purchases | $120 billion |

| Depreciation | $40 billion |

| Consumption | $400 billion |

| Business Investment | $60 billion |

| Exports | $100 billion |

| Imports | $120 billion |

| Income receipts from rest of the world | $10 billion |

| Income payments to rest of the world | $8 billion |

Answer (a): To calculate GDP use the following formula:

Answer (b): To calculate net exports, subtract imports from exports.

Answer (c): To calculate NNP, use the following formula: .. math:

NNP = GDP + Income receipts from the rest of the world

– Income payments to the rest of the world

– Depreciation

4.1.5. Key Concepts and Summary¶

Note

The size of a nation’s economy is commonly expressed as its gross domestic product (GDP), which measures the value of the output of all goods and services produced within the country in a year. GDP is measured by taking the quantities of all goods and services produced, multiplying them by their prices, and summing the total. Since GDP measures what is bought and sold in the economy, it can be measured either by the sum of what is purchased in the economy or what is produced.

Demand can be divided into consumption, investment, government, exports, and imports. What is produced in the economy can be divided into durable goods, nondurable goods, services, structures, and inventories. To avoid double counting, GDP counts only final output of goods and services, not the production of intermediate goods or the value of labor in the chain of production.

4.1.6. Self-Check Questions¶

Todo

Which of the following are included in GDP, and which are not?

- The cost of hospital stays

- The rise in life expectancy over time

- Child care provided by a licensed day care center

- Child care provided by a grandmother

- The sale of a used car

- The sale of a new car

- The greater variety of cheese available in supermarkets

- The iron that goes into the steel that goes into a refrigerator bought by a consumer.

What are the main components of measuring GDP with what is demanded?

4.2. Adjusting Nominal Values to Real Values¶

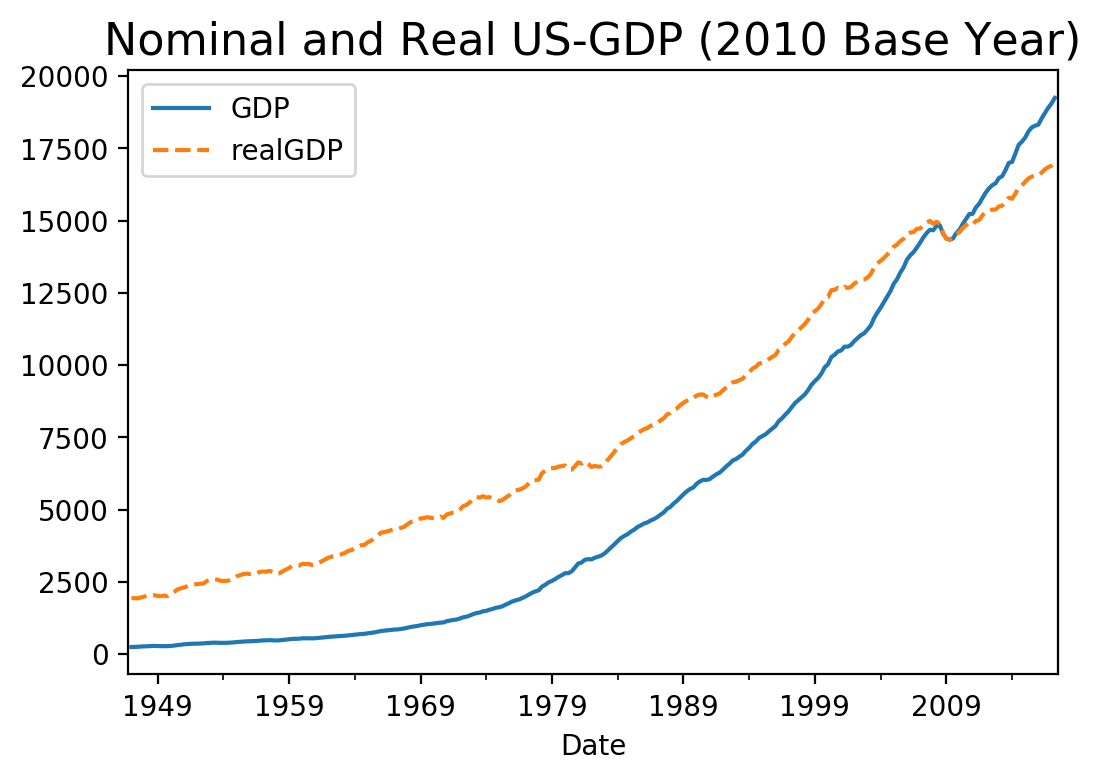

When examining economic statistics, there is a crucial distinction worth emphasizing. The distinction is between nominal and real measurements, which refer to whether or not inflation has distorted a given statistic. Looking at economic statistics without considering inflation is like looking through a pair of binoculars and trying to guess how close something is: unless you know how strong the lenses are, you cannot guess the distance very accurately. Similarly, if you do not know the rate of inflation, it is difficult to figure out if a rise in GDP is due mainly to a rise in the overall level of prices or to a rise in quantities of goods produced. The nominal value of any economic statistic means the statistic is measured in terms of actual prices that exist at the time. The real value refers to the same statistic after it has been adjusted for inflation. Generally, it is the real value that is more important.

4.2.1. Converting Nominal to Real GDP¶

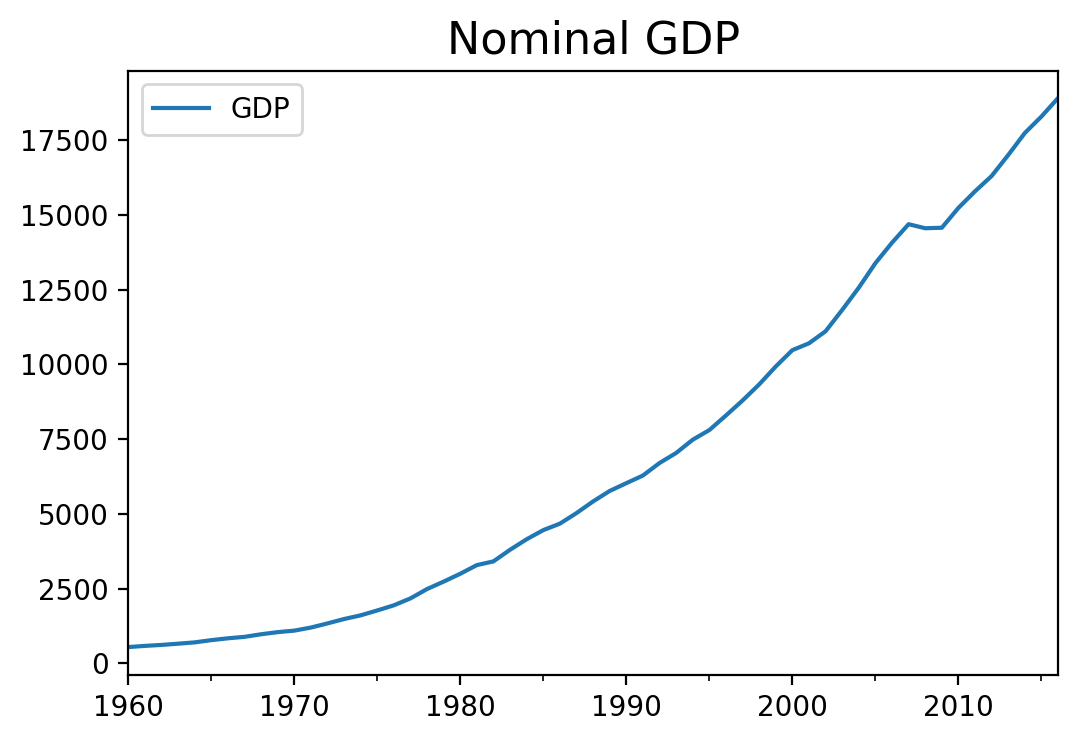

The following Table shows U.S. GDP at five-year intervals since 1960 in nominal dollars; that is, GDP measured using the actual market prices prevailing in each stated year. This data is also reflected in the graph shown in Fig. 4.4.

GDP GDP_Deflator

1960-12-31 541.1 17.560770

1961-12-31 581.6 17.744150

1962-12-31 613.1 17.937390

1963-12-31 654.8 18.214186

1964-12-31 698.4 18.475213

1965-12-31 773.1 18.853339

1966-12-31 834.9 19.481520

1967-12-31 883.2 20.067254

1968-12-31 970.1 20.998745

1969-12-31 1040.7 22.069770

1970-12-31 1091.5 23.182465

1971-12-31 1193.6 24.288301

1972-12-31 1332.0 25.365631

1973-12-31 1479.1 27.077841

1974-12-31 1603.0 29.922347

1975-12-31 1765.9 32.139997

1976-12-31 1938.4 33.814217

1977-12-31 2168.7 36.035692

1978-12-31 2482.2 38.661745

1979-12-31 2730.7 41.985578

1980-12-31 2993.5 46.045345

1981-12-31 3283.5 49.862569

1982-12-31 3407.8 52.483405

1983-12-31 3796.1 54.218382

1984-12-31 4147.6 56.078962

1985-12-31 4453.1 57.737987

1986-12-31 4669.4 58.812268

1987-12-31 5022.7 60.567728

1988-12-31 5412.7 62.858702

1989-12-31 5763.4 65.121692

1990-12-31 6023.3 67.621304

1991-12-31 6279.3 69.643095

1992-12-31 6697.6 71.201829

1993-12-31 7032.8 72.852333

1994-12-31 7476.7 74.376523

1995-12-31 7799.5 75.861767

1996-12-31 8287.1 77.167547

1997-12-31 8788.3 78.394869

1998-12-31 9325.7 79.228083

1999-12-31 9926.1 80.547418

2000-12-31 10472.3 82.593676

2001-12-31 10701.3 84.227055

2002-12-31 11103.8 85.651034

2003-12-31 11816.8 87.346160

2004-12-31 12562.2 90.049031

2005-12-31 13381.6 93.099754

2006-12-31 14066.4 95.579912

2007-12-31 14685.3 97.955549

2008-12-31 14549.9 99.814091

2009-12-31 14566.5 100.169166

2010-12-31 15230.2 101.949260

2011-12-31 15785.3 103.916973

2012-12-31 16297.3 105.934622

2013-12-31 16999.9 107.635859

2014-12-31 17735.9 109.344521

2015-12-31 18287.2 110.512703

2016-12-31 18905.5 112.189492

<matplotlib.text.Text at 0x7ff40260f630>

If an unwary analyst compared nominal GDP in 1960 to nominal GDP in 2010, it might appear that national output had risen by a factor of twenty-seven over this time (that is, GDP of $14,958 billion in 2010 divided by GDP of $543 billion in 1960).

This conclusion would be highly misleading. Recall that nominal GDP is defined as the quantity of every good or service produced multiplied by the price at which it was sold, summed up for all goods and services. In order to see how much production has actually increased, we need to extract the effects of higher prices on nominal GDP. This can be easily done, using the GDP deflator.

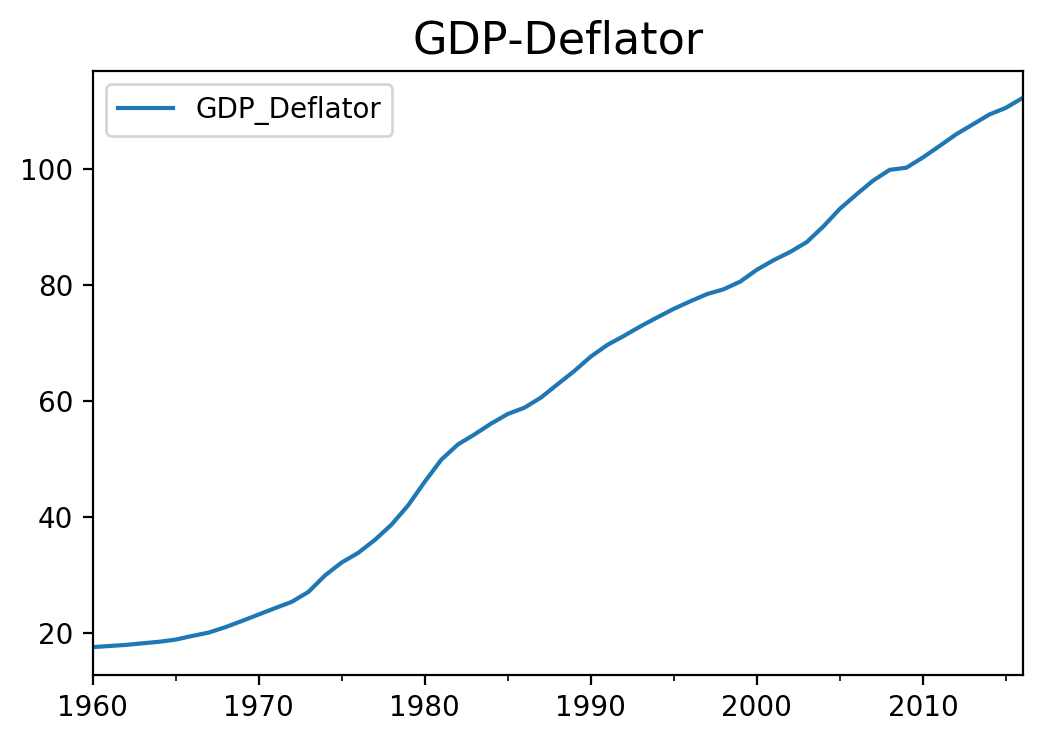

<matplotlib.text.Text at 0x7ff3fade8f98>

GDP deflator is a price index measuring the average prices of all goods and services included in the economy. We explore price indices in detail and how they are computed in Inflation, but this definition will do in the context of this chapter. The data for the GDP deflator are given in the table above and are shown graphically in Fig. 4.5.

Fig. 4.5 shows that the price level has risen dramatically since 1960. The price level in 2010 was almost six times higher than in 1960 (the deflator for 2010 was 110 versus a level of 19 in 1960). Clearly, much of the apparent growth in nominal GDP was due to inflation, not an actual change in the quantity of goods and services produced, in other words, not in real GDP. Recall that nominal GDP can rise for two reasons: an increase in output, and/or an increase in prices.

What is needed is to extract the increase in prices from nominal GDP so as to measure only changes in output. After all, the dollars used to measure nominal GDP in 1960 are worth more than the inflated dollars of 1990—and the price index tells exactly how much more. This adjustment is easy to do if you understand that nominal measurements are in value terms, where

or

Note

Micro Example

Let’s look at an example at the micro level. Suppose the t-shirt company, Coolshirts, sells 10 t-shirts at a price of $9 each.

Then Coolshirts real income is:

In other words, when we compute “real” measurements we are trying to get at actual quantities, in this case, 10 t-shirts.

With GDP, it is just a tiny bit more complicated. We start with the same formula as above:

For reasons that will be explained in more detail below, mathematically, a price index is a two-digit decimal number like 1.00 or 0.85 or 1.25. Because some people have trouble working with decimals, when the price index is published, it has traditionally been multiplied by 100 to get integer numbers like 100, 85, or 125. What this means is that when we “deflate” nominal figures to get real figures (by dividing the nominal by the price index). We also need to remember to divide the published price index by 100 to make the math work.

So the formula becomes:

Now read the following Work It Out feature for more practice calculating real GDP.

<matplotlib.text.Text at 0x7ff3fad30b38>

4.2.2. Key Concepts and Summary¶

Note

The nominal value of an economic statistic is the commonly announced value. The real value is the value after adjusting for changes in inflation. To convert nominal economic data from several different years into real, inflation-adjusted data, the starting point is to choose a base year arbitrarily and then use a price index to convert the measurements so that they are measured in the money prevailing in the base year.

4.2.3. Self-Check Question¶

Todo

- What is the difference between a series of economic data over time measured in nominal terms versus the same data series over time measured in real terms?

- How do you convert a series of nominal economic data over time to real terms?

4.3. Tracking Real GDP over Time¶

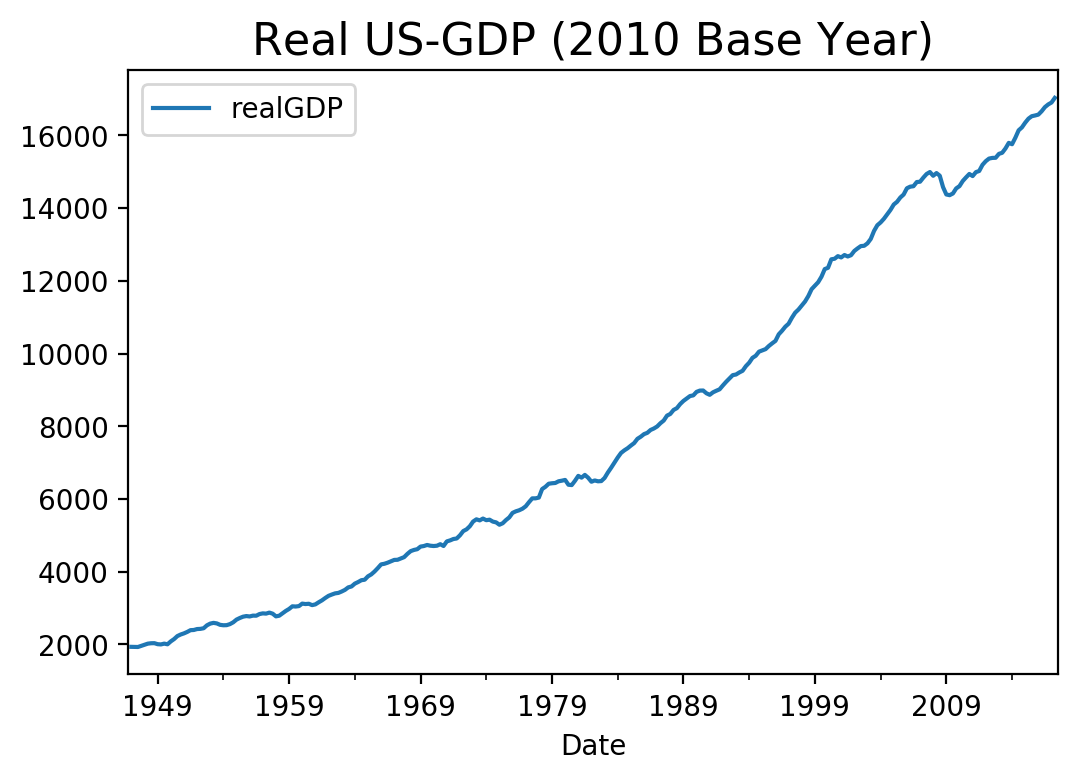

When news reports indicate that “the economy grew 1.2% in the first quarter,” the reports are referring to the percentage change in real GDP. By convention, GDP growth is reported at an annualized rate: Whatever the calculated growth in real GDP was for the quarter, it is multiplied by four when it is reported as if the economy were growing at that rate for a full year.

<matplotlib.text.Text at 0x7ff3fa904080>

fig_RealGDP shows the pattern of U.S. real GDP since 1900. The generally upward long-term path of GDP has been regularly interrupted by short-term declines. A significant decline in real GDP is called a recession. An especially lengthy and deep recession is called a depression. The severe drop in GDP that occurred during the Great Depression of the 1930s is clearly visible in the figure, as is the Great Recession of 2008–2009.

Real GDP is important because it is highly correlated with other measures of economic activity, like employment and unemployment. When real GDP rises, so does employment.

The most significant human problem associated with recessions (and their larger, uglier cousins, depressions) is that a slowdown in production means that firms need to lay off or fire some of the workers they have. Losing a job imposes painful financial and personal costs on workers, and often on their extended families as well. In addition, even those who keep their jobs are likely to find that wage raises are scanty at best—or they may even be asked to take pay cuts.

Table 4.5 lists the pattern of recessions and expansions in the U.S. economy since 1900. The highest point of the economy, before the recession begins, is called the peak; conversely, the lowest point of a recession, before a recovery begins, is called the trough. Thus, a recession lasts from peak to trough, and an economic upswing runs from trough to peak. The movement of the economy from peak to trough and trough to peak is called the business cycle. It is intriguing to notice that the three longest trough-to-peak expansions of the twentieth century have happened since 1960. The most recent recession started in December 2007 and ended formally in June 2009. This was the most severe recession since the Great Depression of the 1930’s.

| Trough | Peak | Months of Contraction | Months of Expansion |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 1900 | September 1902 | 18 | 21 |

| August 1904 | May 1907 | 23 | 33 |

| June 1908 | January 1910 | 13 | 19 |

| January 1912 | January 1913 | 24 | 12 |

| December 1914 | August 1918 | 23 | 44 |

| March 1919 | January 1920 | 7 | 10 |

| July 1921 | May 1923 | 18 | 22 |

| July 1924 | October 1926 | 14 | 27 |

| November 1927 | August 1929 | 23 | 21 |

| March 1933 | May 1937 | 43 | 50 |

| June 1938 | February 1945 | 13 | 80 |

| October 1945 | November 1948 | 8 | 37 |

| October 1949 | July 1953 | 11 | 45 |

| May 1954 | August 1957 | 10 | 39 |

| April 1958 | April 1960 | 8 | 24 |

| February 1961 | December 1969 | 10 | 106 |

| November 1970 | November 1973 | 11 | 36 |

| March 1975 | January 1980 | 16 | 58 |

| July 1980 | July 1981 | 6 | 12 |

| November 1982 | July 1990 | 16 | 92 |

| March 2001 | November 2001 | 8 | 120 |

| December 2007 | June 2009 | 18 | 73 |

A private think tank, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), is the official tracker of business cycles for the U.S. economy. However, the effects of a severe recession often linger on after the official ending date assigned by the NBER.

4.3.1. Key Concepts and Summary¶

Note

Over the long term, U.S. real GDP have increased dramatically. At the same time, GDP has not increased the same amount each year. The speeding up and slowing down of GDP growth represents the business cycle. When GDP declines significantly, a recession occurs. A longer and deeper decline is a depression. Recessions begin at the peak of the business cycle and end at the trough.

4.3.2. Self-Check Question¶

Todo

- What are the typical patterns of GDP for a high-income economy like the United States in the long run and the short run?

- Why do you suppose that u.s. gdp is so much higher today than 50 or 100 years ago?

- Why do you think that GDP does not grow at a steady rate, but rather speeds up and slows down

4.4. Comparing GDP among Countries¶

It is common to use GDP as a measure of economic welfare or standard of living in a nation. When comparing the GDP of different nations for this purpose, two issues immediately arise. First, the GDP of a country is measured in its own currency: the United States uses the U.S. dollar; Canada, the Canadian dollar; most countries of Western Europe, the euro; Japan, the yen; Mexico, the peso; and so on. Thus, comparing GDP between two countries requires converting to a common currency. A second issue is that countries have very different numbers of people. For instance, the United States has a much larger economy than Mexico or Canada, but it also has roughly three times as many people as Mexico and nine times as many people as Canada. So, if we are trying to compare standards of living across countries, we need to divide GDP by population.

4.4.1. Converting Currencies with Exchange Rates¶

To compare the GDP of countries with different currencies, it is necessary to convert to a “common denominator” using an exchange rate, which is the value of one currency in terms of another currency. Exchange rates are expressed either as the units of country A’s currency that need to be traded for a single unit of country B’s currency (for example, Japanese yen per British pound), or as the inverse (for example, British pounds per Japanese yen). Two types of exchange rates can be used for this purpose, market exchange rates and purchasing power parity (PPP) equivalent exchange rates. Market exchange rates vary on a day-to-day basis depending on supply and demand in foreign exchange markets. PPP-equivalent exchange rates provide a longer run measure of the exchange rate. For this reason, PPP-equivalent exchange rates are typically used for cross country comparisons of GDP. Exchange rates will be discussed in more detail in Exchange Rates and International Capital Flows. The following Work It Out feature explains how to convert GDP to a common currency.

4.4.2. GDP Per Capita¶

The U.S. economy has the largest GDP in the world, by a considerable amount. The United States is also a populous country; in fact, it is the third largest country by population in the world, although well behind China and India. So is the U.S. economy larger than other countries just because the United States has more people than most other countries, or because the U.S. economy is actually larger on a per-person basis? This question can be answered by calculating a country’s GDP per capita; that is, the GDP divided by the population.

GDP per capita = GDP/population GDP per capita = GDP/population

The second column of Table lists the GDP of the same selection of countries that appeared in the previous Tracking Real GDP over Time and Table, showing their GDP as converted into U.S. dollars (which is the same as the last column of the previous table). The third column gives the population for each country. The fourth column lists the GDP per capita. GDP per capita is obtained in two steps: First, by dividing column two (GDP, in billions of dollars) by 1000 so it has the same units as column three (Population, in millions). Then dividing the result (GDP in millions of dollars) by column three (Population, in millions).

4.4.3. Key Concepts and Summary¶

Note

Over the long term, U.S. real GDP have increased dramatically. At the same time, GDP has not increased the same amount each year. The speeding up and slowing down of GDP growth represents the business cycle. When GDP declines significantly, a recession occurs. A longer and deeper decline is a depression. Recessions begin at the peak of the business cycle and end at the trough.

4.4.4. Self-Check Question¶

Todo

- What are the two main difficulties that arise in comparing the GDP of different countries?

- Is it possible for GDP to rise while at the same time per capita GDP is falling? Is it possible for GDP to fall while per capita GDP is rising?

4.5. How Well GDP Measures the Well-Being of Society¶

The level of GDP per capita clearly captures some of what we mean by the phrase “standard of living.” Most of the migration in the world, for example, involves people who are moving from countries with relatively low GDP per capita to countries with relatively high GDP per capita.

“Standard of living” is a broader term than GDP. While GDP focuses on production that is bought and sold in markets, standard of living includes all elements that affect people’s well-being, whether they are bought and sold in the market or not. To illuminate the gap between GDP and standard of living, it is useful to spell out some things that GDP does not cover that are clearly relevant to standard of living.

4.5.1. Limitations of GDP as a Measure of the Standard of Living¶

While GDP includes spending on recreation and travel, it does not cover leisure time. Clearly, however, there is a substantial difference between an economy that is large because people work long hours, and an economy that is just as large because people are more productive with their time so they do not have to work as many hours. The GDP per capita of the U.S. economy is larger than the GDP per capita of Germany, as was shown in [link], but does that prove that the standard of living in the United States is higher? Not necessarily, since it is also true that the average U.S. worker works several hundred hours more per year more than the average German worker. The calculation of GDP does not take the German worker’s extra weeks of vacation into account.

While GDP includes what is spent on environmental protection, healthcare, and education, it does not include actual levels of environmental cleanliness, health, and learning. GDP includes the cost of buying pollution-control equipment, but it does not address whether the air and water are actually cleaner or dirtier. GDP includes spending on medical care, but does not address whether life expectancy or infant mortality have risen or fallen. Similarly, it counts spending on education, but does not address directly how much of the population can read, write, or do basic mathematics.

GDP includes production that is exchanged in the market, but it does not cover production that is not exchanged in the market. For example, hiring someone to mow your lawn or clean your house is part of GDP, but doing these tasks yourself is not part of GDP. One remarkable change in the U.S. economy in recent decades is that, as of 1970, only about 42% of women participated in the paid labor force. By the second decade of the 2000s, nearly 60% of women participated in the paid labor force according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. As women are now in the labor force, many of the services they used to produce in the non-market economy like food preparation and child care have shifted to some extent into the market economy, which makes the GDP appear larger even if more services are not actually being consumed.

GDP has nothing to say about the level of inequality in society. GDP per capita is only an average. When GDP per capita rises by 5%, it could mean that GDP for everyone in the society has risen by 5%, or that of some groups has risen by more while that of others has risen by less—or even declined. GDP also has nothing in particular to say about the amount of variety available. If a family buys 100 loaves of bread in a year, GDP does not care whether they are all white bread, or whether the family can choose from wheat, rye, pumpernickel, and many others—it just looks at whether the total amount spent on bread is the same.

Likewise, GDP has nothing much to say about what technology and products are available. The standard of living in, for example, 1950 or 1900 was not affected only by how much money people had—it was also affected by what they could buy. No matter how much money you had in 1950, you could not buy an iPhone or a personal computer.

In certain cases, it is not clear that a rise in GDP is even a good thing. If a city is wrecked by a hurricane, and then experiences a surge of rebuilding construction activity, it would be peculiar to claim that the hurricane was therefore economically beneficial. If people are led by a rising fear of crime, to pay for installation of bars and burglar alarms on all their windows, it is hard to believe that this increase in GDP has made them better off. In that same vein, some people would argue that sales of certain goods, like pornography or extremely violent movies, do not represent a gain to society’s standard of living.

4.5.2. Does a Rise in GDP Overstate or Understate the Rise in the Standard of Living?¶

The fact that GDP per capita does not fully capture the broader idea of standard of living has led to a concern that the increases in GDP over time are illusory. It is theoretically possible that while GDP is rising, the standard of living could be falling if human health, environmental cleanliness, and other factors that are not included in GDP are worsening. Fortunately, this fear appears to be overstated.

In some ways, the rise in GDP understates the actual rise in the standard of living. For example, the typical workweek for a U.S. worker has fallen over the last century from about 60 hours per week to less than 40 hours per week. Life expectancy and health have risen dramatically, and so has the average level of education. Since 1970, the air and water in the United States have generally been getting cleaner. New technologies have been developed for entertainment, travel, information, and health. A much wider variety of basic products like food and clothing is available today than several decades ago. Because GDP does not capture leisure, health, a cleaner environment, the possibilities created by new technology, or an increase in variety, the actual rise in the standard of living for Americans in recent decades has exceeded the rise in GDP.

On the other side, rates of crime, levels of traffic congestion, and inequality of incomes are higher in the United States now than they were in the 1960s. Moreover, a substantial number of services that used to be provided, primarily by women, in the non-market economy are now part of the market economy that is counted by GDP. By ignoring these factors, GDP would tend to overstate the true rise in the standard of living.

4.5.3. GDP is Rough, but Useful¶

A high level of GDP should not be the only goal of macroeconomic policy, or government policy more broadly. Even though GDP does not measure the broader standard of living with any precision, it does measure production well and it does indicate when a country is materially better or worse off in terms of jobs and incomes. In most countries, a significantly higher GDP per capita occurs hand in hand with other improvements in everyday life along many dimensions, like education, health, and environmental protection.

No single number can capture all the elements of a term as broad as “standard of living.” Nonetheless, GDP per capita is a reasonable, rough-and-ready measure of the standard of living.

Note

HOW IS THE ECONOMY DOING? HOW DOES ONE TELL?

To determine the state of the economy, one needs to examine economic indicators, such as GDP. To calculate GDP is quite an undertaking. It is the broadest measure of a nation’s economic activity and we owe a debt to Simon Kuznets, the creator of the measurement, for that. The sheer size of the U.S. economy as measured by GDP is huge—as of the third quarter of 2013, $16.6 trillion worth of goods and services were produced annually. Real GDP informed us that the recession of 2008–2009 was a severe one and that the recovery from that has been slow, but is improving. GDP per capita gives a rough estimate of a nation’s standard of living. This chapter is the building block for other chapters that explore more economic indicators such as unemployment, inflation, or interest rates, and perhaps more importantly, will explain how they are related and what causes them to rise or fall.

4.5.4. Key Concepts and Summary¶

Note

GDP is an indicator of a society’s standard of living, but it is only a rough indicator. GDP does not directly take account of leisure, environmental quality, levels of health and education, activities conducted outside the market, changes in inequality of income, increases in variety, increases in technology, or the (positive or negative) value that society may place on certain types of output.

4.5.5. Self-Check Question¶

Todo

- List some of the reasons why GDP should not be considered an effective measure of the standard of living in a country.

- How might a “green” GDP be measured?